World War II Chronicle: May 17, 1943

Click here for TODAY’S NEWSPAPER

Front page: Last night, 19 specially modified Avro Lancaster bombers took off to attack four dams along the Ruhr River in western Germany. A secret unit codenamed “Squadron X” had spent the last few months figuring out the best way to destroy an enemy dam. Crews had to release their barrel-shaped weapon 60 feet above the water at 232 miles per hour for it to skip across the water until it hits the dam. That level of precision wouldn’t be easy for a modern-day pilot using GPS navigation.

The Lancaster crews used old-fashioned instruments. Their “speedometer” measured how fast they are moving in relation to the air around them, not actual ground speed. So they would have to have an idea of the winds above the target. And their altimeters rely on barometric pressure, which varies along the route. Finding their way across hundreds of miles over enemy territory at night to find the target, on the right approach vector at the right speed and altitude seems nothing short of miraculous. Especially when they had to fly through heavy fog while avoiding obstacles and flak from enemy anti-aircraft gunners. Stay tuned for details…

Two of President Roosevelt’s sons are mentioned on the bottom of the second page. A plane carrying Northwest African Photographic Reconnaissance Wing commander Col. Elliot Roosevelt ran into a parked transport after a cross-wind landing in Tunisia. Neither Roosevelt nor his pilot were injured, but two war correspondents in the transport were hurt. And Col. James Roosevelt is in San Diego to treat a case of malaria he contracted in the Solomons. He relinquished command of the 4th Marine Raider Battalion last month…

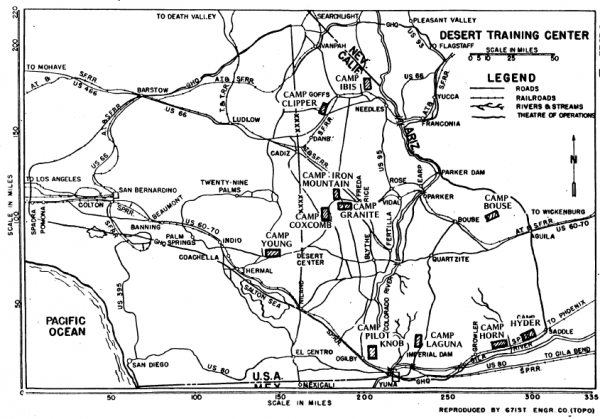

Page seven reports that Generaloberst Jurgen von Arnim, the commanding general of Axis forces in Tunisia, has landed in England. He is one of now 27 general officers that have surrendered to the Allies in North Africa… A story on the same page discusses the massive Desert Training Center. Maj. Gen. George S. Patton established the network of camps, airfields, and maneuver areas last year to train American soldiers for desert warfare.

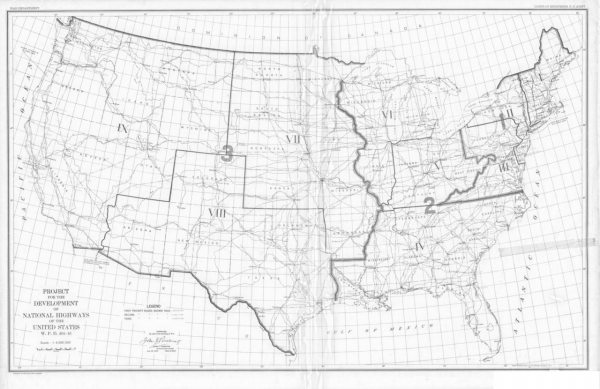

Considering the map above, you will probably notice there are no interstates. Dwight Eisenhower’s interstate highway system becomes law in 1956 and will take decades to complete. He is not the first general behind a cross-country network of highways: Army Chief of Staff Gen. John J. Pershing had engineers create a proposal of the road network needed to sustain another war. World War I demands exceeded America’s railroad capacity, and a future war would require even more shipping.

Pershing’s map reflected only the military’s requirements such as fending off an invasion and moving essential materials like coal and iron. Civilian economic needs were not a factor so the “Pershing Map” looks very different than our roadmap 100 years later. Before the military could pitch the need for a road system, they had to show how badly the United States needed one. Eisenhower –then a brevet lieutenant colonel — rode along with a convoy that traveled 3,000 miles from Washington, D.C. to San Francisco. Most of the trip was along unpaved roads, and while the soldiers hoped to average 15 miles per hour, they only were able to travel 5 m.p.h…

George Fielding Eliot column on page 10… Sports section begins on page 14.

Roving Reporter by Ernie Pyle

NORTHERN TUNISIA — (By Wireless) — Much of our Northern Tunisian mountain fighting has been done at night and in the dark of the moon too. It had always been a mystery to me how troops could move on foot in total darkness over rough, pathless country that is completely strange to them. Having now moved with them on several night marches I know how it is done.

The going is just as difficult as I had thought it would be. The pace is slow — one mile an hour in moving up into the lines would be a good speed. The soldiers usually go single file. They don’t march, they just walk. Each man has to pick and feel for his own footholds. Sure, you fall down. You step into a hole or trip on a telephone wire, or stub your toe on a rock, and down you go. but you get right up again and go on. You try to keep close enough to the man in front so that you can see his form dimly and follow him. Keeping your course at night is as difficult as navigating at sea, for it is total darkness and you have no landmarks to go by.

Capt. E.D. Driscoll, of New York, says:

“We have Gremlins in the infantry too. And the meanest Gremlin is the one who moves mountains. You start for a certain hill in the dark, you check everything carefully as you go along, and then when you get there some Gremlin has moved the damn mountain and you can’t find it anywhere.”

Here’s how they do these night marches:

At the head of the column are guides who have reconnoitered the route in daytime patrols and memorized the main paths, hills and gullies. In addition, and officer with compass is at the head of the column, and in case of doubt they get down and throw a blanket over themselves for blackout, and look at the compass by flashlight.

Other guides are posted along the line to keep the rear elements from straying off on side paths. Furthermore, the leaders mark the trail as they go. They usually do this by leaving strips of white mine-marking tape lying on the ground every hundred yards or so. On our march they had run out of white tape so they used surgeons’ gauze instead. Sometimes they mark the trail by wrapping toilet paper around rocks and leaving them lying on the path.

In spite of all this, two or three dim-witted guys out of every company get lost, and spend the next couple of days wandering around the hills asking everybody they come onto where their company is.

A column advancing into new country strings its own telephone wire. You probably know that Army telephone wire is simply strung on the ground. We are now using very light wire, and even a small person like myself can carry a half-mile reel of it under his arm.

On our first night march we carried two miles of phone wire with us. At the end of a half-mile reel we’d contact a field telephone and call back to battalion headquarters to tell them how far we’d got, what we had seen and heard, and whether there was any opposition. As soon as another half-mile was strung the phone would be advanced.

The Germans have been adept at one thing up here. That is in digging and camouflaging their gun positions. I know one case where we captured a dug-in 88-millimeter gun while driving the Germans off a hill, and after the battle was over and we came back to get the big gun we couldn’t find the damn thing ourselves, though it was obviously still right there.

Also they dug in machine-gun snipers on the hillsides and left them there. When the rest of the Germans withdrew these guys would be hidden in the rocky hillsides right among our own troops. After we had occupied the hill they would fire on our troops to the rear, and generally make pests of themselves. We had an awful time finding them. I know of two machine-gunners who stayed in their little dugouts and kept firing for three days after we had occupied their hill, despite the fact that our troops still bivouacked all over the hillside, living within a few feet of them, walking past or over their gun positions scores of times a day.

They dig a good-sized hole and cover it with the rocks that abound on these hillsides, leaving a little hole just big enough to fire through. They keep a few days’ rations, and just stay there until captured. The place looks like any other of thousands of places on the hillside. You can walk past it or stand on it and not know what’s beneath you. Once you do know, you find that you can’t get the gunners out without practically tearing the rocks out by hand.

One of these smart guys had a circus for three days shooting at me till they finally dug him out. I’ll tell you about that tomorrow, as I’m shaking badly right at the moment.

Evening star. (Washington, D.C.), 17 May 1943. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress.

https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83045462/1943-05-17/ed-1/