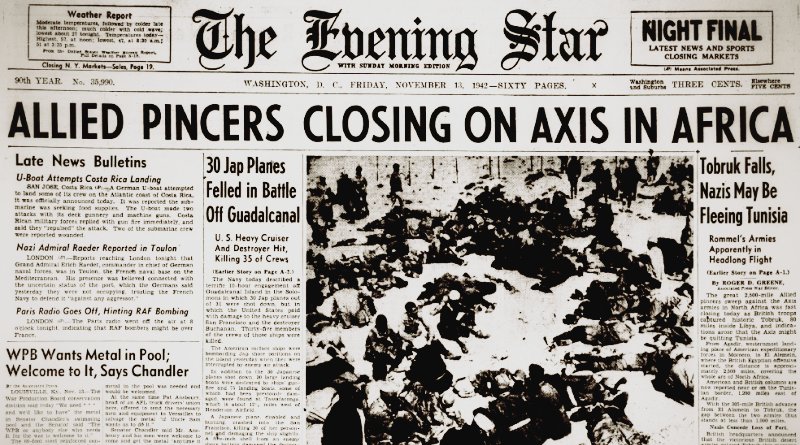

World War II Chronicle: November 13, 1942

Click here for TODAY’S NEWSPAPER

Capt. William T. Cherry Jr., who piloted the B-17 carrying Capt. Eddie Rickenbacker over the South Pacific has been rescued, three weeks after ditching his plane in the ocean. Crews are searching the area for additional survivors (see pages one and two)…

A photo of newly promoted Lt. Gen. Mark Clark from his West Point days is found on page eight, alongside that of his son William D. Clark who is a plebe at the U.S. Military Academy and will graduate in 1945. Grandfather Col. Charles C. Clark also graduated West Point. Clark will earn the Distinguished Service Cross, two Silver Stars, and three Purple Hearts in Korea… Lt. Charles L. McClure, Crew 7 navigator of the Doolittle Raid on Tokyo, tells his story on page eight…

George Fielding Eliot column on page 12… Former American Expeditionary Force commander Gen. John J. Pershing has written a letter to the French people asking them to join the fight against the Axis (see page 28)… The “Philippine Escape” series continues on page 42…

Sports section begins on page 54, and pictured are Tulane’s Marty Comer and George Poschner of Georgia. Porschner would have been high school teammates with his roommate and fellow Bulldog teammate Frankie Sinkwich, but he was too small to play at the time. It may be hard to believe, but one of the top receivers in the game is new to the sport. Soon both players will be in uniform: Porschner as an infantry platoon leader and Comer will play for the Second Air Force Superbombers before joining the Buffalo Bisons of the All-America Football Conference.

Just a few days ago one of Sinkwich and Poschner’s former Georgia teammates, center Thomas E. “Tommy” E. Witt, was killed in action when his B-25 Mitchell was shot down. Witt was a pilot in the 434th Bombardment Squadron…

Wake Forest’s Red Cochran is pictured on page 55. His college career is interrupted when he becomes a bomber pilot in the Fourteenth Air Force, flying missions in the China-Burma-India Theater. He is drafted in the eighth round of the 1944 NFL Draft, but after the war Cochran finishes up at Wake Forest. He plays three seasons for the Chicago Cardinals and also plays a season of minor league baseball in 1948.

Roving Reporter by Ernie Pyle

IN ENGLAND — Our Flying Fortress crews are usually made up of four commissioned officers and six sergeants. The pilot, co-pilot, navigator and bombardier are usually lieutenants.

The aerial engineer, the radio operator, his assistant, and three full-time gunners are all sergeants. Actually, if they’re in the thick of a fight, everybody in the plane is firing a gun except the pilot and co-pilot.

We don’t have sergeant-pilots, as the British do. There is less formality in the Air Forces than in other branches of the Army. I’ve been around bomber stations for a week and haven’t seen more than half a dozen salutes. Riding back in the trucks with the bomber crews, you wouldn’t know from their actions who was officer and who was no-com. But once off duty, there isn’t much association between officers and enlisted men.

During flight, all members of the crew are in touch with each other over the plane’s intercomm (inter-communications system), with each man wearing a headphone and hearing the captain’s voice directing him, or the warnings from other crew members.

Any man who sees a plane approaching reports it so that all can hear. In the various gun stations inside a plane, you’ll notice a red line painted on one side of the framework just ahead of the gun, and a green line on the other side. That’s a permanent guide to avoid confusion of direction.

Because the crew, you see, is facing in all directions. The tail-gunner is just the reverse of the captain. If they used left or right, various crew members might look in the wrong direction. So the warnings are always given “Plane coming in on the green (or red),” and then everybody knows in which direction to look.

The air crews do not take lunches with them as the British night bombers do, for their trips up to now are so short it isn’t necessary.

They leave behind them every single personal thing; they have nothing in their pockets and no identification except the dog-tags around their necks.

As they file out of the locker room after dressing for a flight, each man is handed a small white sack with his name on it. In this sack he puts all his money, keys, personal papers and what not. The sack is returned to him when he comes back.

The boys say that once in the air you’re usually too busy — even during the trip over — to be concerned about your safety. They are on the alert from the moment they cross the English coast until they cross it coming back. Every man is at his guns, continuously rotating his turret to watch the sky.

It is only when they’re once more over “dear old England” that they relax, and the gunners are called off and can go into the radio room where it’s a little warmer.

The boys get terribly cold in these high altitude flights. True, they wear electrically heated suits, but nothing has ever been found to keep them really comfortable.

They have to have the side doors open for the two waist-guns, consequently the temperature in the fuselage is the same as outdoor. And already they’ve hit temperatures at these high altitudes of 48 below zero. They say temperatures at similar high altitudes are much lower here than at home.

Of course they have to use oxygen in their high bombing altitudes. If one man is wounded and another has to go to his aid, the samaritan switches his tube to a small portable tank of oxygen which he carried on his back. For you can keep conscious up there without oxygen for about 20 seconds only.

One crew I know starts using oxygen while still under 5000 feet. The boys move around and work their arms as much as possible, to get themselves acclimated. That way they feel more normal when they get high and are existing solely on oxygen. I spoke to a flight surgeon about it and he said that didn’t make any difference, but if the boys THOUGHT it did then it sure was okay with him.

Evening star. (Washington, D.C.), 13 November 1942. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress.

https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83045462/1942-11-13/ed-1/