World War II Chronicle: December 6, 1941

Click here for TODAY’S NEWSPAPER

The front page reports that Detroit Tiger slugger Hank Greenberg was released yesterday from the Army… On page two, the Sugar Bowl will host an inter-service championship football game between Third Army and Pensacola Naval Air Station on Jan. 3… Sports section begins on page 20, which mentions that the Chicago Bears are having a homecoming after their game tomorrow against the Chicago Cardinals. Among those expected to attend are legends Red Grange and Bronko Nagurski…

80 years ago, Lt. Gen. Walter C. Short’s Hawaiian Department was on “Alert 1” status with its aircraft parked wingtip-to-wingtip. Commanders believed the Imperial Japanese Navy wouldn’t risk attacking Pearl Harbor, and sabotage was the primary security concern.1 From 7 December 1941: The Air Force Story:

“… ammunition not needed for immediate training would be boxed and stored in central locations difficult for an enemy to reach and destroy. Thus, when the attack began, most antiaircraft ammunition was boxed and stored far away from the actual gun locations. At Wheeler Field, maintenance personnel not only removed the machine gun ammunition from the aircraft, they removed it from the belts so it could be boxed and stored in one location. Coincidentally, the Japanese hit this central location (a hangar) during the attack and destroyed most of the ammunition stored there. Aircraft, during Alert One, would be centrally located as close together as possible for ease in guarding them.”

“After being notified about an impending air attack against Hawaii, the Hawaiian Department would go to Alert Two. At this level, measures used in Alert One would remain in effect; in addition, personnel would activate the Air Warning Center, arm fighter aircraft and place them on alert, launch long-range reconnaissance, and arm and deploy antiaircraft units. From this intermediate level, the entire Hawaiian Department would go to Alert Three when invasion seemed imminent. At level three, the command functions would move to underground facilities and available personnel would deploy to prepared beach defenses.”

Seems like a decent enough plan, and looking at things from the perspective of what they knew versus what we now know, safeguarding against Japanese saboteurs instead of bracing for a strategically impractical air attack makes sense. But when it comes to plans — especially in the military — what can go wrong, will. And at the worst possible time.

The Army’s aging B-18 fleet didn’t have sufficient range to patrol the waters around Hawaii, so reconnaissance duty fell to the Navy’s 60 PBY Catalinas. While that may sound like a lot of planes, only a few planes and crews can fly at a time; there is a maintenance and rest cycle, plus with a war on the horizon, you don’t want to wear out patrol planes before the shooting even started.

Considering a 500-mile search radius, and even with eliminating the eastern half of the circle (it’s highly unlikely an enemy would go past their target before attacking), that’s still nearly half a million square miles of ocean. Commanders had to prioritize areas, so the flights going out are to the south, towards the closest Japanese bases that could support an invasion — the exact opposite direction the First Air Fleet was coming from.

1: Oahu had a substantial Japanese population

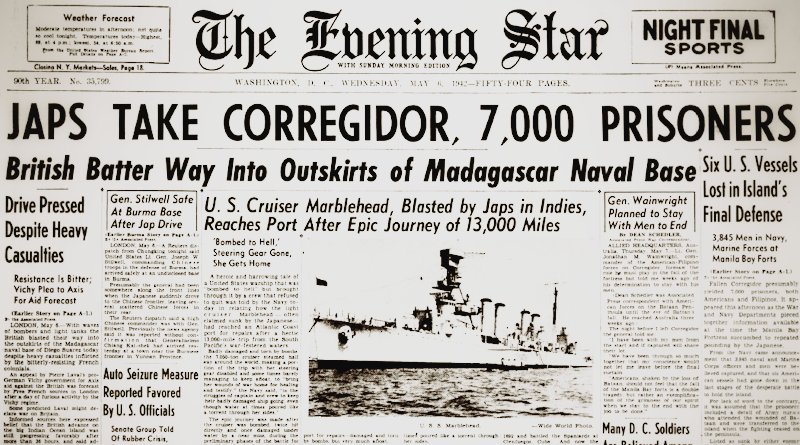

Evening star. (Washington, D.C.), December 6, 1941. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress.

https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83045462/1941-12-06/ed-1/