World War II Chronicle: December 29, 1941

Click here for TODAY’S NEWSPAPER

1st Lt. Boyd “Buzz” Wagner has become the United States’ first ace of the war and is discussed on page 11… Sports section begins on page 14…

After World War I, the Joint Planning Committee (the predecessor to today’s Joint Chiefs of Staff) created a series of strategies should we find ourselves at war against various countries. War Plan BLACK was for a war with Germany, ORANGE for Japan, GREEN for Mexico, GOLD for France, YELLOW for China, several colors for operations in Central and South America or the Caribbean, and the list keeps going.

We even had War Plan RED for war with the United Kingdom in addition to several sub-plans for wars against British territories like Australia, Canada, Ireland, and India. Plus, there was War Plan RED-ORANGE in the event of a war against both the UK and Japan.

These plans assumed the United States was fighting alone and on one front. Before Japan’s surprise attacks at Pearl Harbor and the Philippine Islands, the committee wanted a plan in the event of a war in both Europe and the Pacific. War Plan RAINBOW was the result, and it had several contingencies:

- RAINBOW 1: defensive war with no allies, protecting the Western Hemisphere north of the 10th parallel (south)

- RAINBOW 2: the same scenario, but allied with France and the UK

- RAINBOW 3: same as ORANGE, only an initial priority of securing the area defined in RAINBOW 1

- RAINBOW 4: same as RAINBOW 1, only covering the entire Western Hemisphere

- RAINBOW 5: allied with France and Britain, with American troops conducting offensive operations — this is the plan we based our World War II strategy on

With Nazi Germany invading Poland, Hitler’s non-intervention pact with the Soviet Union, and Japan’s war with China, RAINBOW 5 seemed to be the most likely playbook, and it was sub-divided into additional possibilities:

- Plan ABLE: War with Japan and no American allies

- Plan BAKER: War with Japan and Britain as our ally

- Plan CHARLIE: War against Japan, who allies with Germany and Italy; no American allies

- Plan DOG: Above scenario, but with Britain as an ally

- Plan EASY: Remain out of the war and defend the Western Hemisphere

78 years ago at this time, Winston Churchill had crossed the Atlantic to set up a temporary headquarters in the White House to confer with President Franklin Roosevelt. First Lady Eleanor wondered how someone could smoke and drink as much as Churchill and stay up so late, while still being healthy. Churchill made himself quite at home (roaming around in his pajamas) as he and Roosevelt hammered out a unified grand strategy. Of all the possible contingencies, RAINBOW-5 DOG, with an emphasis on “Europe first,” was the winner.

Incidentally, Churchill recently learned that his nephew Esmond M.D. Romilly had perished1 along with the rest of his crew in the North Sea on 30 November 1941 during a raid on Hamburg, Germany. The 22-year-old Pilot Officer served as a navigator and was assigned to the Royal Air Force’s No. 58 Squadron.

Orange is the New Rainbow

As our military switched from ORANGE to RAINBOW, U.S. commanders had to rearrange objectives and reposition forces to fit the new strategy. Under ORANGE-3, Gen. Douglas MacArthur (commander of the U.S. Army Forces in the Far East) would fight a series of delaying actions, holding off the Japanese long enough for supplies to be moved to Corregidor and Bataan. RAINBOW-5 meant that American and Filipino troops now had to defeat a Japanese landing force on the beach.

Under RAINBOW, there would be no withdrawal to Bataan, and there would be no resupply or relief forces. MacArthur’s troops had to hold the beaches. At all costs.

Among the many important things one learns in the military, you realize through experience that a) no plan survives first contact with the enemy, and b) what can go wrong will — at the worst possible time (Murphy’s Law). Holding the beach at all costs sounds like a workable plan to generals and admirals in comfy leather chairs in Washington, D.C., but what if the Far East Air Force that your strategy relies on for air support is wiped out in the first days of the war? What if the Philippine troops won’t stand and fight when targeted by Japanese air and artillery attacks?

That is exactly what happened and Gen. MacArthur had to quickly figure out how to fight with both hands tied behind his back.

The Filipino troops guarding the Lingayen coast could not keep Lt. Gen. Masaharu Homma’s 14th Army from establishing a beachhead when the main landings happened on 22 December. MacArthur’s forces outnumbered Homma’s, but his Philippine Army troops, with the exception of the valiant Philippine Scouts of the 26th Cavalry Regiment, broke and fled the battlefield. Maj. Gen. Johnathan M. Wainwright ordered his North Luzon Force to fall back and form a defensive line at the Agno River, where the World War I veteran commander hoped to stage a counterattack.

Considering the disappointing performance of his Philippine Army troops, MacArthur realized that instead of sacrificing his best troops (the Philippine Division, which was manned by more dependable Americans and Filipino Scouts) to a likely doomed counteroffensive, he had to revert to the original Plan ORANGE-3 strategy. Wainwright’s forces would fight a two-week delaying action along five successive defensive lines, hopefully buying the rest of the Far East forces enough time to fall back.

On Christmas Eve, MacArthur began moving his headquarters to the island fortress of Corregidor while his troops removed their equipment from Manila.

1: See page eight of the Dec. 4, 1941 Chronicle

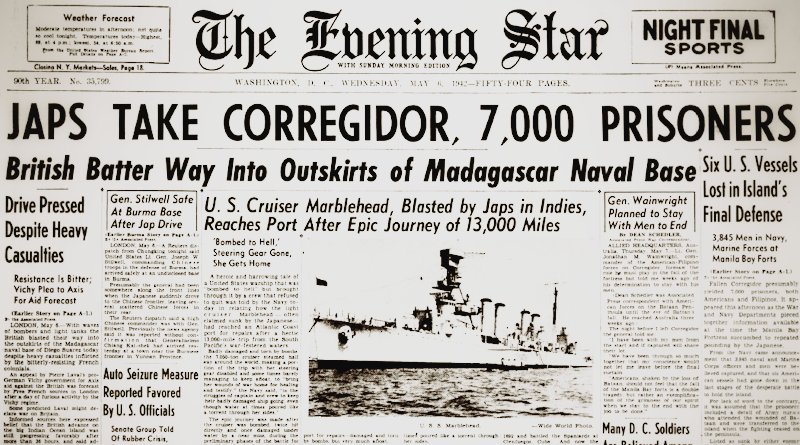

Evening star. (Washington, D.C.), December 29, 1941. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress.

https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83045462/1941-12-29/ed-1/