World War II Chronicle: July 19, 1943

Click here for TODAY’S NEWSPAPER

A large formation of American heavy bombers has targeted Rome in a daylight raid… Pictured on page eight is former U.S. Senator (and future Governor of Vermont) Ernest W. Gibson Jr., the 43rd Infantry Division’s intelligence officer. Col. Gibson is being treated for wounds received during the Rendova campaign…

George Fielding Eliot column on page 10… Sports on page 15, which reports that former St. Louis Cardinals second baseman Creepy Crespi, now playing for the Fort Riley Cavalry Replacement Training Center, broke his leg when another player slid into his leg trying to break up a double play. This will be the first of three times he breaks his left leg during his time in uniform. He endures 23 surgeries and a nurse will accidentally overdose Crespi with boric acid which badly burns him and leaves him with a permanent limp.

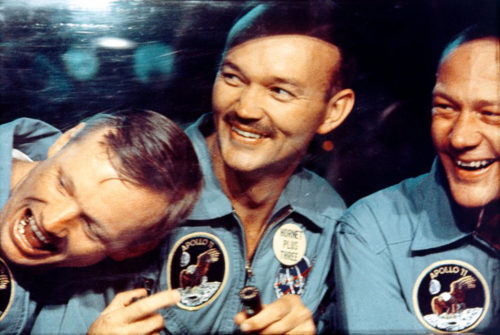

On this day in 1969 an astronaut named Michael Collins is orbiting the moon aboard the Apollo 11 spacecraft. But why bring up Michael Collins, who is just 12 years old at this stage of the war? Because his father, brother, and uncle were officers during World War II. Father James Lawton Collins served as John J. Pershing’s aide during the Philippine-American War, the Punitive Expedition into Mexico, and the World War. Now a major general, he recently served as the Commanding General of the U.S. Army’s Puerto Rico Department, and will spend the remainder of the war in various stateside commands.

Brother James Lawton Collins Jr. is assistant operations officer for IX Corps and will later fight in Europe. Their uncle J. Lawton Collins was Commanding General of the Hawaiian Department last year before becoming the Army’s youngest division commander at 46. His 25th Infantry Division fought on Guadalcanal and are currently engaged in New Georgia. All Collinses are graduates of the U.S. Military Academy, and Michael will also attend West Point (Class of ’52).

Roving Reporter by Ernie Pyle

ABOARD A U.S. NAVY SHIP OF THE INVASION FLEET — Before sailing on the invasion our ship had been lying far out in the harbor tied to a buoy for several days. Several times a day “General Quarters” would sound and the crew would dash to their battle stations but always it what a photo plane or perhaps one of our own.

Then we moved into a pier. That very night the raiders came and our ship got its baptism of fire — she lost her virginity, as the sailors put it. I had got out of bed at 3 a.m. as usual to stumble sleepily up to the radio shack to go over the news reports which the wireless had picked up. There were several radio operators on watch and we were sitting around drinking coffee while we worked. Then around 4 a.m. all of a sudden “General Quarters” sounded. It was still pitch dark. The whole ship came to life with a scurry and rattling, sailors dashing to stations before you’d have thought they could get their shoes on.

Shooting had already started around the harbor so we knew this time it was real. I kept on working and the radio operators did too, or rather tried to work. So many people were going in and out of the radio shack that we were in darkness half the time since the lights automatically go off when the door opened.

Then the biggest guns of our ship let loose. They made such a horrifying noise we thought we’d been hut by a bomb every time they went off. Dust and Debris came drifting down from the ceiling to smear up everything. Nearby bombs shook us up, too.

One by one the electric light bulbs were shattered from the blasts. The thick steel walls of the cabin shook and rattled as though they were tin. The entire vessel shivered under each blast. The harbor was lousy with ships and they were all shooting. The raiders were dropping flares all over the sky and the searchlights on the warships were fanning the heavens.

Shrapnel rained down on the decks making a terrific clatter. All this went on for an hour and a half. When it was over and everything was added up we found four planes had been shot down. Our casualties were negligible and no damage was done the ship except little holes from near-misses. Three men on our ship had been wounded.

Best of all, we were credited with shooting down one of the planes.

Now this raid of course was only one of scores of thousands that have been conducted in this war. Standing alone it wouldn’t even be worth mentioning. I’m mentioning it to show you what a little taste of the genuine thing can do for a bunch of young Americans.

As I wrote the other day our kids on this ship had never been in action. The majority of them were strictly wartime sailors, still half-civilian in character. They’d never been shot at, never shot one of their own guns except in practice and because of this they had been very sober, a little unsure and more than a little worried about the invasion ordeal that lay so near ahead of them. And then, all within and hour and a half, they became veterans. Their zeal went up like one of those shooting graph lines in the movies when business is good. Boys who had been all butterfingers were loading shells like machinery after 15 minutes when it became real. Boys who previously had gone through their routine lifelessly were now yelling with bitter seriousness, “Dammit, can’t you pass them shells faster.”

The gunnery officer, making his official report to the captain, did it in these gleefully, robust words:

“Sir we got the son of a bitch.”

One of my friends aboard ship is Norman Sombery, aerographer, third class, of Miami. We had been talking the day before and he told me how he had gone two years to the University of Georgia studying journalism and wanted to get in it after the war. I noticed he always added: “If I live through it.”

Just at dawn, as the raid ended, he came running up to me full of steam and yelled, “Did you see that plane go down smoking! Boy, if I could get off the train at Miami right now with the folks and my girl there to meet me I couldn’t be happier than I was when I saw we’d got that guy.”

It was worth a day’s pay to be on this ship the day after the raid. All days long the sailors went gabble, gabble, gabble, each telling the other how they did it, what they saw, what they thought. After the raid a great part of the reluctance to start for the unknown vanished, their guns had become their pals, the enemy became real and the war came alive for them and they didn’t fear it so much anymore. This crew of sailors had just gone through what hundreds of thousands of other soldiers and sailors already had experienced — the conversion from peaceful people into fighters. There’s nothing especially remarkable about it but it is moving to be on hand and see it happen.

Evening star. (Washington, D.C.), 19 July 1943. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress.

https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83045462/1943-07-19/ed-1/