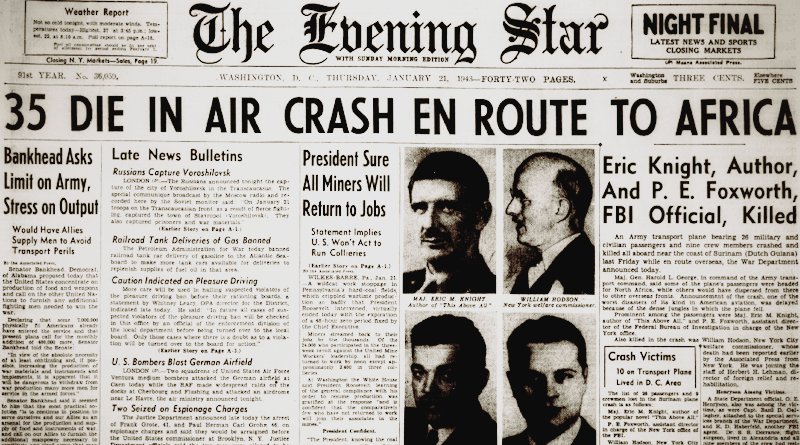

World War II Chronicle: January 21, 1943

Click here for TODAY’S NEWSPAPER

Today’s front page reports the loss of a DC-4 off the coast of Dutch Guinea. 35 passengers and crew were killed in what was the deadliest American aviation disaster of its time and the first loss of a Douglas DC-4. The plane and crew belonged to Transcontinental & Western Air was flying under contract for the Army Air Force’s Air Transport Command. Oddly enough, there was a rumor that a bomb may have been stowed aboard which forced the pilot to divert to Trinidad before the incident. Two other planes in the same formation reported what could have been an enemy submarine firing at the cargo plane when it went down, but an investigation into the crash site concluded that the plane was brought down by mechanical failure.

Maj. Eric M. Knight, an British-born officer in the U.S. Army was among the passengers. When Eric’s father died, his mother moved the family to Russia and she became a governess for the Imperial family in Russia. He fought with Princess Patricia’s Light Canadian Infantry during World War I, while both of his brothers served in the Pennsylvania National Guard and were killed on the same day during the First World War. Knight later joined the U.S. Army Reserve as an artillery officer. He wrote several books, including This Above All and Lassie Come-Home (yes, he created the famous Collie).

Also killed were two FBI agents on a secret mission: Assistant Director Percy E. Foxworth and Special Agent Harold Haberfeld. Lt. Gen. Dwight Eisenhower requested the FBI send a team to investigate an American citizen who may have collaborated with the Axis in North Africa… Eddie Rickenbacker’s copilot continues his story on page four… George Fielding Eliot column on page 12… Sports section begins on page 19

Roving Reporter by Ernie Pyle

A FORWARD AIRDROME IN FRENCH NORTH AFRICA, (By Wireless) — Everything is temporary around this airdrome near the front. It is in violent contrast to the fine airports at home and to the permanent stations we have in England.

Gone are the luxurious English lounges, billiard rooms and bar, and the twice daily custom of tea, which are part of every RAF station. Here there is no bar, no tea, no billiards. A few of the troops throw footballs around in the evening for relaxation.

There is no place for the officers to sit down together during their off hours unless they sit on the ground or on empty gasoline cans. The commanding officer’s desk is merely a board laid across four empty wooden crates.

The supply rooms for rations and plane parts are just little corrals built up of empty gasoline tins filled with sand and laid like bricks. I think the American Army would collapse all over the world without its empty gasoline tins. They’ve become a truer symbol of American than the eagle.The briefing room for bomber crews is a large tent with maps of enemy territory tacked on a board that is nailed to two posts set in the ground. In front of the board is a little platform made of gasoline tins sprinkled with sand. The crews just stand there and listen to their instructions.

Somehow it’s not quite the way we picture it from books and movies. In those picturizations we see only the actual takeoffs — everything else is blotted out of our minds, and the whole field seems to be devoted solely to starting the bombers on their mission.

Actually, the greater portion of the men at this airdrome know nothing about a mission until they see the planes start forming up in the air above. All work goes on as usual. The start of a mission is only another cog in the immense job of the day.

A cover patrol of fighter planes hovers above just in case. When the mission is finally formed the local fighter bunch comes in and a new batch takes off to go along with the bombers.

Work is routine while they are away, but everybody is watchful when the time nears for them to start coming back. It is true that people watch and count as the planes start appearing on the horizon. But this is a useless pastime, for not half a dozen people on the field know exactly how many planes really are due back. With the air constantly full of planes, and so many circling and waiting and new ships arriving from other fields, it is almost impossible to count correctly the number of planes starting on a mission. Nevertheless, the ground crews try, and they start counting as the planes come home.

There are other things they look for just as intently when the planes return. They look for feathered propellers, and for planes sort of straggling and limping along. They look for returning fighters to peel off and do a victory roll across the field, showing that they’ve shot down a German. When this happens you hear cheers all over the field.

If any planes fail to return the news gets around the field by word of mouth in a few hours. People are sorry, but actual grief never shows.There is never a moment during daylight when there are not planes in the air. The first patrols take off before dawn and the last ones land after dark. All day there is a ceaseless coming and going. New bunches of replacement planes arrive and depart in workhorse manner. Casuals drop in just a few days out of America, England or India. Actually the air above seems much like Bolling field at Washington.

It is hard to believe the whole thing was set up with one purpose only — destruction and death. It is just as hard to believe that destruction and death can likewise come to us out of the same blue sky. But as one officer said:

“We’ve got to realize it, for believe me everything is for keeps now.”

Evening star. (Washington, D.C.), 21 January 1943. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress.

https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83045462/1943-01-21/ed-1/