World War II Chronicle: July 5, 1941

Click here for TODAY’S NEWSPAPER

A few weeks after retiring as a baseball player, former St. Louis Cardinals pitching legend Dizzy Dean has also brought his short-lived coaching career with the Chicago Cubs to an end. The paper reports that he suited up as a first base coach for today’s game against the Pittsburgh Pirates, but will be climbing the stairs to the announcer’s booth for his first game on July 10.

While it may sound odd that Dean is calling games for St. Louis’ Falstaff Brewing Co. (since-defunct, but was then among the top breweries in the United States), in that era, baseball was great marketing for beer makers. In fact, Busch Stadium — there have been three — was so-named because Major League Baseball wouldn’t let owners name stadiums after alcoholic beverages, keeping August A. Busch Jr. from naming old Sportsman’s Park to Budweiser Stadium. So he named the stadium after himself then created “Busch (Bavarian) Beer.”

Dean will spend the next 25 years in the booth, doing play-by-play for the St. Louis Browns, Cardinals, and Yankees before calling the NBC and CBS Games of the Week. Here’s this from Dean’s page at the Society for American Baseball Research:

Dean hit the airwaves on July 10, 1941, broadcasting a Yankees-Browns game in his debut. He was a fan favorite, even though he distorted the English language. Although some chalked it up to his lack of an education, others felt that he made mistakes on purpose to draw attention to himself. “Diz always knew what he was doing,” said [legendary Yankees sportscaster] Mel Allen. “The things he came up with — a guy sludding into third — they were professional. I’ll never forget: He said ‘slid’ correctly, by mistake, and he corrected himself. He wanted to goof up — it was a part of the vaudeville.” […] Wrote J.G. Taylor Spink, editor of The Sporting News, “Contrary to the thought of some, Dizzy is no clown over the air. True, he uses an informal, colorful style, establishing his own rules of grammar. But this only adds to the interest of his broadcasts, which give listeners an accurate picture of what is transpiring on the diamond.”

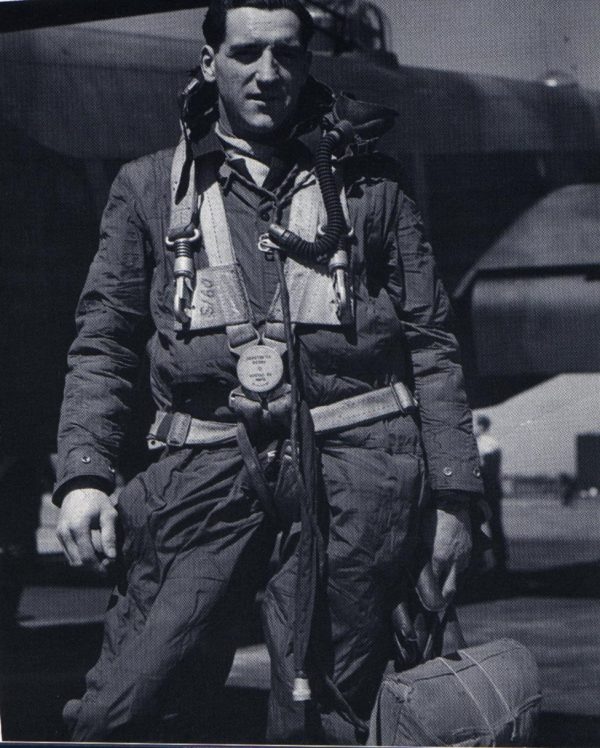

Dean saw Vince DiMaggio go 0-4 with an intentional walk against his Cubbies, but younger brother Joe extended his hitting streak to a record-setting 46 games off Philadelphia’s Phil Marchildon. The Canadian-born righthander wins 17 of the last-place A’s 55 games in 1942, but spends the next two seasons with the Royal Canadian Air Force. While he did occasionally appear at a ballgame in England, he spent his time as a gunner on a Halifax bomber. On his 26th combat mission, enemy guns set Marchildon’s aircraft on fire and the pilot ordered the seven-man crew to bail out.

Marchildon and the navigator were the only airmen to make it out alive, jumping into the frigid waters of the Baltic Sea. Marchildon was rescued from freezing to death by Danish fishermen, but spent the next nine months as a prisoner in Stalag Luft III. He also survived the Death March as the war drew to a close. During his comeback game on August 29, 1945 — “Phil Marchildon Night” at Philadelphia’s Shibe Park — he allowed just two hits in five innings. Despite being haunted by his wartime experiences, Marchildon put together a 19-9 record in 1947, despite the A’s finishing 22 games below .500.

Page two mentions a father saving his two children from drowning at a San Diego beach. Actor Pat O’Brien and family were “splashing about” with Ronald Reagan when a cross-current swept O’Brien’s children into a hole. Reagan, a former lifeguard, was too far away to assist, but O’Brien managed to rescue his exhausted children from the surf. The two actors recently starred in Knute Rockne, All American (1940), which is where Reagan (who portrayed George Gipp) picked up his nickname and campaign slogan, which came from the “Win one for the Gipper” line in the movie.

Notre Dame halfback Jack Chevigny, who yelled “That’s one for the Gipper!” as he scored the winning touchdown against Army at Yankee Stadium on Nov. 19, 1928, would go on to become a Marine officer and was killed in action during the Iwo Jima landing. 36 years old in 1943, a knee injury from his football days prevented Chevigny from enlisting, but he was later drafted into the Army. Following basic training, he requested a transfer to the Marine Corps Reserve and he was commissioned a second lieutenant. He coached Camp Pendleton’s football team before requesting overseas duty, serving as a liaison officer with the 27th Marines.

Evening star. (Washington, D.C.), 5 July 1941. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress.

https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83045462/1941-07-05/ed-1/