World War II Chronicle: February 22, 1944

Click here for TODAY’S NEWSPAPER

The front page reports that the U.S. Navy has sent 92 Japanese warships to the bottom of the Pacific Ocean and page two says Eniwetok Island has been captured… George Fielding Eliot says the Japanese fleet is collapsing in his column on page six…

Sports on page eight, featuring a Grantland Rice column on early American presidents who were sportsmen… Electronic warfare in the 1940s? Yes, radar equipped B-17 crews nicknamed “Pathfinders” led nighttime raids into occupied Europe, and a correspondent shares the story on page 15…

Cmdr. John T. “Tommy” Blackburn and his “Jolly Rogers” squadron are discussed on page 25. Fighting Squadron 17 (VF-17) is the second Navy outfit to fly the Vought F4U Corsair and they are really giving the Japanese the business. In just over two months of combat VF-17 has shot down 152 enemy aircraft and by war’s end will hold the record for most victories of any Navy squadron.

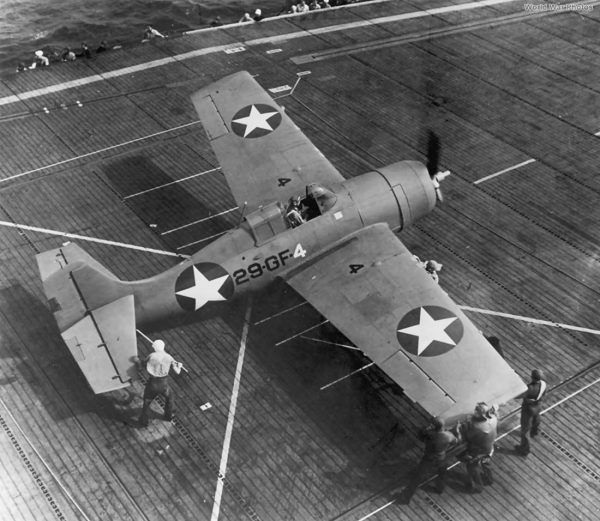

A graduate of the Naval Academy (Class of ’33), Blackburn was flying Brewster F2A Buffaloes out of Opa Locka Naval Air Station when war broke out. After lobbying for a combat assignment the Navy named him commanding officer of the new Auxiliary Fighting Squadron 29 (VGF-29), which received its baptism of fire on D-Day of Operation TORCH. Blackburn took off from the escort carrier USS Santee and led a combat air patrol mission protecting the transports and carriers. Unfortunately the flattop’s vectoring equipment failed, resulting in the loss of seven F4s. Lt. George N. Trumpeter was killed when he ditched into the sea (the destroyer escort USS Trumpeter was named in his honor) and Blackburn spent the next three days adrift until rescued by a destroyer. Some of the Blackburn’s Wildcats made it to Morocco and were briefly held prisoner by the French.

Weeks later the Navy made him skipper of another newly formed squadron — the Jolly Rogers. Earlier this month Blackburn shot down four A6M “Zekes,” bringing his total confirmed kills to 11. His father Capt. Paul P. Blackburn (USNA ’04) retired in 1939 but is now the director of the 3rd District’s Naval Reserve.

Roving Reporter by Ernie Pyle

IN ITALY — Most infantry companies in the front lines now are composed largely of replacements, as they are in all armies after more than a year of fighting.

Some of these replacements have been here only a few weeks. Others came so long ago they are now as seasoned as the original men of the company.

The new boys are afraid, of course, and very eager to hear and to learn. They hang onto the words of the old-timers. I suppose during the last few days before your first battle is one of the worst ordeals of a lifetime. Now and then one will crack up before he has ever gone into action.

One day I was wandering through an olive grove talking with some of these newer kids when I saw a soldier, sitting on the edge of his foxhole, wearing a black silk opera hat. That’s what I said — an opera hat.

The owner was Pvt. Gordon T. Winter. He’s a Canadian. His father owns an immense sheep ranch near Lindberg, Alberta, 200 miles northeast of Edmonton.

Pvt. Winter said he found the top hat in a demolished house in a nearby village and just thought he’d bring it along. “I’m going to wear it in the next attack,” he said. “The Germans will think I’m crazy, and they’re afraid of crazy people.”

In the same foxhole was a thin, friendly boy who seemed hardly old enough to be in high school. There was fuzz instead of whiskers on his face and he had that eager-to-be-nice attitude that marked him as not long away from home.

This was Pvt. Robert Lee Whichard of Baltimore. It turned out that he was only 18. He has been overseas only since early winter. He has seen action already. He was laughing when telling me about the first time he was in battle.

Apparently it was a pretty wild melee, and ground was changing hands back and forth. Pvt. Whichard said he was lying on the ground shooting, “or maybe not shooting. I don’t know.” because he admits he was pretty scared.

He happened to look up and here were two German soldiers walking past him. Bob said he was so scared he just rolled over and lay still. Pretty soon mortar shells began dropping and the Germans decided to retire. So they came back past him, and he still lay there playing dead until finally they were gone and he was safe.

Bob says the other night he dreamed his feet were so cold that he ran to the battalion aid station and there were his mother and sister fixing some hot food over a wood fire for him and poking up the fire so he could warm his feet. But before either the food or his feet were warm he woke up — and his feet were still cold.

Another soldier came past and said he’d dreamed the night before that he was home and his mother was cooking pork chops by the tub-full for him to eat. This one was Cpl. Pamal Meena, whose father is a Syrian minister in Cleveland.

The post office system has broken down as far as Cpl. Meena is concerned. He has been overseas five months and has never got a letter. The corporal has not been in combat but is ready for it. He says he hasn’t decided whether he is going to be a minister, like his father, but he has taken to reading his Bible since he came to war.

Cpl. Meena wants me to come past Cleveland after the war and have a good old Syrian meal at his house. He says I won’t have to remember his name — just remember that his father is the only Syrian preacher in Cleveland and find him that way.

One day I was walking through another olive orchard which held the 34th Division Headquarters, and I noticed a soldier under a tree cleaning a sewing machine.

This was Pvt. Leonard Vitale of Council Bluffs, Ia. He’s an old-timer in the division. As I looked around I saw a couple of other sewing machines sitting on boxes. “Good Lord, what are you doing?” I asked. Starting a sewing-machine factory?

Vitale said no, he was just getting set to do altering and mending for division headquarters. The first two sewing machines he had bought from Italians, and an AMG officer had given him the newest machine. It was a Singer, in an elaborate mahogany cabinet.

Vitale said he wasn’t an expert tailor but had picked up some of the rudiments during three and a half years he’d spent in the CCC and thought he would do all right and make a little money on the side. As I walked away he called out:

“I’ll have this war sewed up in a couple of months.”

I grabbed a rifle from a nearby MP and shot the punster through and through before he had me in stitches.

IN ITALY — The company commander said to me, “Every man in this company deserves the Silver Star.” We walked around in the olive grove where the men of the company were sitting on the edges of their foxholes, talking or cleaning their gear.

“Let’s go over here,” he said. “I want to introduce you to my personal hero.”

I figured that the Lieutenant’s “personal hero,” out of a whole company of men who deserved the Silver Star, must be a real soldier indeed.

Then the company commander introduced me to Sergt. Frank Eversole, who shook hands sort of timidly and said, “Pleased to meet you,” and then didn’t say any more.

I couldn’t tell by his eyes and his slow and courteous speech when he did talk that he was a Westerner. Conversation with him was sort of hard, but I didn’t mind his reticence for I know how Westerners like to size people up first.

The Sergeant wore a brown stocking cap on the back of his head. His eyes were the piercing kind. I noticed his hands — they were outdoor hands, strong and rough.

Later in the afternoon I came past his foxhole again, and we sat and talked a little while alone. We didn’t talk about the war, but mainly about our West, and just sat and made figures on the ground as we talked.

We got started that way, and in the days that followed I came to know him well. He is to me, and to all those with whom he serves, one of the great men of the war.

Frank Eversole’s nickname is “Buck.” The other boys in the company sometimes call him “Buck Overshoes,” simply because Eversole sounds a bit like “overshoes.”

But he was a cowboy before the war. He was born in the little town of Missouri Valley, Ia., and his mother still lives there. But Buck when West on his own before he was 16, and ever since has worked as a ranch hand. He is 23 and unmarried.

He worked a long time around Twin Falls, Idaho, and then later down in Nevada. Like so many cowboys, he made the rodeos a season. He was never a star or anything. Usually he just rode the broncs out of the chute for pay — $7.50 a ride. Once he did win a fine saddle. He has ridden at Cheyenne and the other big rodeos.

Like any cowboy, he loves animals. Here in Italy one afternoon Buck and some other boys were pinned down inside a one-room stone shed by terrific German shellfire. As they sat there, a frightened mule came charging through the door. There simply wasn’t room inside for men and mule both, so Buck got up and shooed him out the door. Thirty feet from the door a direct hit killed the mule. Buck has always felt guilty about it.

Another time Buck ran onto a mule that was down and crying in pain from a bad shell wound. Buck took his .45 and put a bullet through his head. “I wouldn’t have shot him except he was hurtin’ so,” Buck says.

Buck Eversole has the Purple Heart and two Silver Stars for bravery. He is cold and deliberate in battle. His commanders depend more on him than any other man. He has been wounded once, and had countless narrow escapes. He has killed many Germans.

He is the kind of man you instinctively feel safer with than with other people. He is not helpless like most of us. He is practical. He can improvise, patch things, fix things.

His grammar is the unschooled grammar of the plains and the soil. He uses profanity, but never violently. Even in the familiarity of his own group his voice is always low. He is such a confirmed soldier by now that he always says “sir” to any stranger. It is impossible to conceive of his doing anything dishonest.

After the war Buck will go back West to the land he loves. He wants to get a little place and feed a few head of cattle, and be independent.

“I don’t want to just be a ranch hand no more,” he says. “It’s all right and I like it all right, but it’s a rough life and it don’t get you nowhere. When you get a little older you kinda like a little place of your own.”

Buck Eversole has no hatred for Germans. He kills because he’s trying to keep alive himself. The years roll over him and the war becomes his only world, and battle his only profession. He armors himself with a philosophy of acceptance of what may happen.

“I’m mighty sick of it all,” he says very quietly, “but there ain’t no use to complain. I just figure it this way, that I’ve been given a job to do and I’ve got to do it. And if I don’t live through it, there’s nothing I can do about it.”

Top-heat-wearing Pvt. Winter served in the U.S. Army and survived the war, passing away in 1980. Pfc. Leonard L. Vitale passed away in 1962. Frank Eversole was wounded three times during the war, earning the Bronze Star in addition to his two Silver Stars. TSgt. Eversole ended up a police officer after the war and passed in 1967. The company commander showing Pyle around is 1st. Lt. John J. Sheehy, who himself earned the Silver Star in 1943.

Evening star. (Washington, D.C.), 22 February 1944. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress.

https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83045462/1944-02-22/ed-1/