World War II Chronicle: January 15, 1944

Click here for TODAY’S NEWSPAPER

George Fielding Eliot discusses the Eastern Front on page six… Back in August we reported that an Army K9 dog named Chips was decorated for valor on Sicily. Now we learn on page eight that the Army is looking into whether or not the German Shepherd has in fact been decorated for valor… Sports on page 12, and Rogers Hornsby looks to be headed to the Mexican Baseball League, where he will reportedly serve as manager for the Veracruz Azules. Hornsby wrapped up his big league career seven years ago (in 1937) with the St. Louis Browns.

Roving Reporter by Ernie Pyle

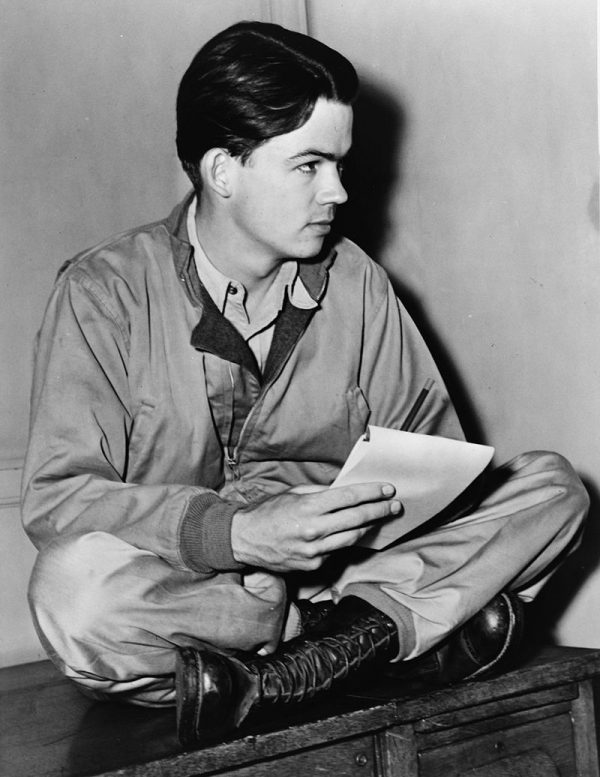

IN ITALY — Sgt. Bill Mauldin appears to us over here to be the finest cartoonist the war has produced. And that’s not merely because his cartoons are funny, but because they are also terribly grim and real.

Mauldin’s cartoons aren’t about training — camp life, which you at home are best acquainted with. They are about the men in the line — the tiny percentage of our vast Army who are actually up there in that other world doing the dying. His cartoons are about the war.

Mauldin’s central cartoon character is a soldier, unshaven, unwashed, unsmiling. He looks more like a hobo than like your son. He looks, in fact, exactly like a doughfoot who has been in the lines for two months. And that isn’t pretty.

Mauldin’s cartoons in a way are bitter. His work is so mature that I had pictured him as a man approaching middle age. Yet he is only 22, and he looks even younger. He himself could never have raised the heavy black beard of his cartoon dogface. His whiskers are soft and cant, his nose is upturned good-naturedly, and his eyes have a twinkle.

His maturity comes simply from a native understanding of things, and from being a soldier himself for a long time. He has been in the Army three and a half years.

Bull Mauldin was born in Mountain Park, N.M. He now calls Phoenix, Ariz. his home base, but we of New Mexico could claim him without much resistance on his part.

Bill has drawn ever since he was a child. He always drew pictures of the things he wanted to grow up to be, such as cowboys and soldiers, not realizing that what he really wanted to become was a man who draws pictures.

He graduated from high school in Phoenix at 17. It took a year at the Academy of Fine Arts in Chicago, and at 18 was in the Army. He did 64 days of K.P. duty in his first four months. That fairly cured him of a lifelong worship of uniforms.

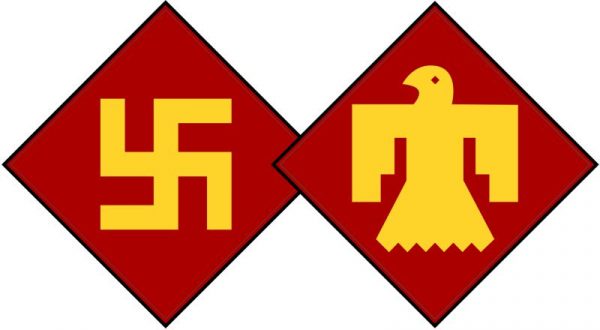

Mauldin belongs to the 45th Division. Their record has been a fine one, and their losses have been heavy. Mauldin’s typical grim cartoon soldier is really a 45th Division infantryman, and he is one who has truly been through the mill.

Mauldin was detached from straight soldier duty after a year in the infantry, and put to work on the division’s weekly paper. His true war cartoons started in Sicily and have continued on through Italy, gradually gaining recognition. Capt. Bob Neville, Stars and Stripes editor, shakes his head with a veteran’s admiration and says of Mauldin:

“He’s got it. Already he’s the outstanding cartoonist of the war.”

Mauldin works in a cold, dark little studio in the back of Stars & Stripes’ Naples office. He wears silver-rimmed glasses when he works. His eyes used to be good, but he damaged them in his early Army days by drawing for too many hours at night with poor light.

He averages about three days out of 10 at the front, then comes back and draws up a large batch of cartoons. If the weather is good he sketches a few details at the front. But the weather is usually lousy.

“You don’t need to sketch details anyhow,” he says. “You come back with a picture of misery and cold and danger in your mind and you don’t need any more details than that.”

His cartoon in Stars & Stripes is headed “Up Front . . . By Mauldin.” The other day some soldier wrote in a nasty letter asking what the hell did Mauldin know about the front.

Stars & Stripes printed the letter. Beneath it in italics they printed a short editor’s note: “Sgt. Bill Mauldin received the Purple Heart for wounds received while serving in Italy with Pvt. Blank’s own regiment.”

That’s know as telling ’em.

Bill Mauldin is a rather quiet fellow, a little above medium size. He smokes and swears a little and talks frankly and pleasantly. He is not eccentric in any way.

Even though he’s just a kid he’s a husband and father. He married in 1942 while in camp in Texas and his son was born last August 20 while Bill was in Sicily. his wife and child are living in Phoenix now. Bill carries pictures of them in his pocketbook.

Unfortunately for you and Mauldin both, the American public has no opportunity to see his daily drawings. But that isn’t worrying him. He realizes this is his big chance.

After the war he wants to settle again in the Southwest, which he and I love. He wants to go on doing cartoons of the same guys who are now fighting in the Italian hills, except that by then they’ll be in civilian clothes and living as they should be.

The cartoonist drew the ire of Gen. George S. Patton by openly mocking his spit-and-polish culture for Third Army soldiers. Patton wanted to throw Mauldin’s “unpatriotic anarchist […] ass in jail” and ban Stars & Stripes, but Gen. Dwight Eisenhower intervened. Decades later Mauldin said, “I always admired Patton. Oh, sure, the stupid bastard was crazy. He was insane. He thought he was living in the Dark Ages. Soldiers were peasants to him. I didn’t like that attitude, but I certainly respected his theories and the techniques he used to get his men out of their foxholes.”

In the 1930s, Mauldin’s 45th Infantry Division logo was actually a swastika — an homage to the Southwest’s Native American population. It was later changed to the Thunderbird when the Nazi Party adopted the symbol.

Evening star. (Washington, D.C.), 15 January 1944. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress.

https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83045462/1944-01-15/ed-1/