World War II Chronicle: August 27, 1943

Click here for TODAY’S NEWSPAPER

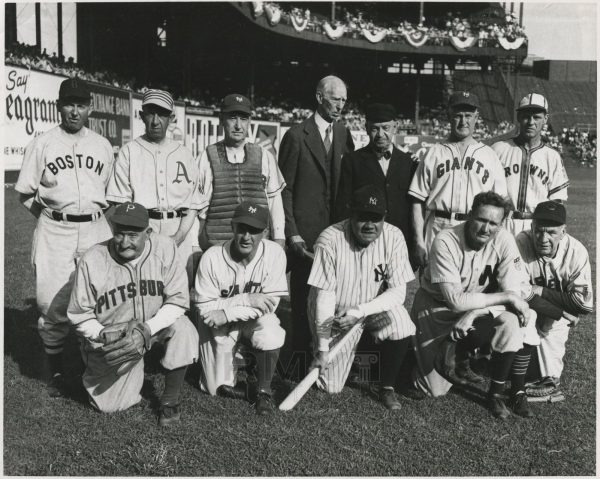

George Fielding Eliot column on page six… Sports section is on page 10, and the Polo Grounds hosted a War Bond Jubilee featuring Babe Ruth, Walter Johnson, and several other Hall of Fame players.

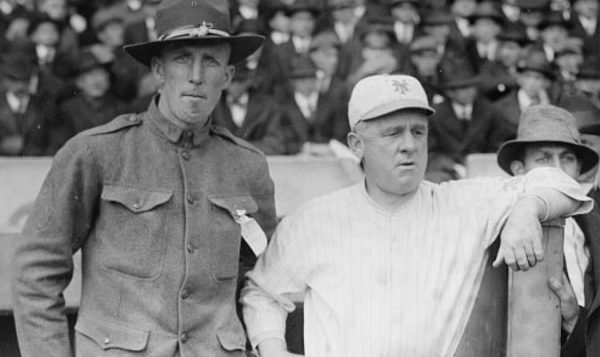

The “Old Arbitrator” — Bill Klem — served as umpire and Connie Mack was manager. This would be Babe Ruth’s last home run and the last time Walter Johnson pitched.

The Yankees, Giants, and Dodgers put together a squad to face a team of soldiers from New Cumberland (Pa.) Reception Center, who had some other Army all-stars mixed in. Capt. Hank Gowdy, who is the athletic officer at Fort Benning, managed the Army team, which featured former major leaguers Hank Greenberg, Sid Hudson, Johnny Beazley, Billy Hitchcock, Birdie Tebbetts, and Enos Slaughter. Casey Stengel heads the New York team. Both skippers served during World War I. The event sold $800 million in war bonds…

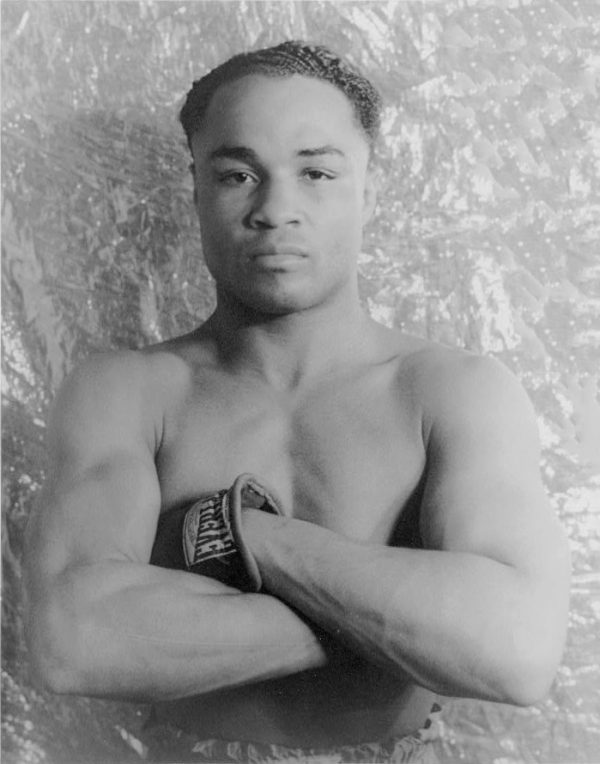

Meanwhile, two of the greatest boxers of all time face each other tonight in Madison Square Garden” Corporal Sugar Ray Robinson and former featherweight, lightweight, and welterweight champion Henry Armstrong. Robinson’s first pro match was the undercard for Armstrong’s main event fight on Oct. 4, 1940, in which the underdog Fritzie Zivic took the world welterweight title from Hammerin’ Hank. It was Armstrong’s 19th title defense. Armstrong and Zivic rematched twice: Zivic won in 1941 (by then he had already lost the title) and Armstrong won in 1942. Robinson is just 22 years old and he has a 44-1 record. Armstrong (134-18-8) is 33 years old…

Also, the University of Alabama has announced they will not be able to field a football team this year.

Roving Reporter by Ernie Pyle

SOMEWHERE IN SICILY — The awarding of bravery medals is a rather dry and formal thing and I never heretofore bothered to cover any of these festivities but the other night I learned that three old friends of mine were in a group to be decorated so I went down to have supper with them and see the show.

My three friends are Lieut. Col. Harry Gosless Columbus, Oo., Maj. John Hurley San Francisco, and Maj. Mitchell Mabardy, of Assonet, Mass. Gosless is headquarters commandant of a certain outfit, and Hurley and Marbardy are provost marshals in charge of military police.

They were camped under big beech trees on the Sicilian hillside just back of the battlefront, I went down about 5:30 and found my friends sitting on folding chairs under a tree outside their tent, looking at fighting far ahead through field glasses.

Any soldier will verify that one of the outstanding traits of any war are those incongruous interludes of quiet that pot up now and then in the midst of the worst horror. This evening was one of them. Our troops were in a bitter fight for the town of Tronia, standing up like a great rock pinnacle on a hilltop a few miles ahead.

That afternoon our high command had called for an all-out air and artillery bombardment on the city. When it came it was terrific. Planes by the score roared over and dropped their deadly loads, and as they left our artillery put down the most devastating barrage we’ve ever used against a single point, even outdoing any shooting we did in Tunisia.

Up there in Troina a complete holocaust took place. Through our glasses the old city seemed to fly apart. Great clouds of dust and black smoke rose into the sky until the whole horizon was loaded and fogged. Our biggest bombs exploded with such roars that we felt the concussion clear back where we were and our artillery in a great semi-circle crashed and roared like some gigantic inhuman beast that had broken loose and was out to destroy our world.

Germans by the hundred were dying up there at the end of our binocular vision and all over the mountainous horizon the world seemed to be ending. And yet we sat there in easy chairs under a tree sipping cool drinks, relaxed and peaceful at the end of a day’s work. Sitting there looking at it as though we were spectators at a play. It just didn’t seem that it couldn’t be true.

After a while we walked up to the officers’ mess in a big tent under a tree and ate captured German steak which tasted very good indeed.

Then after supper the six men and three officers who were to receive awards lined up outside the tent. They were nine legitimate heroes all right. I know, for I was in the vicinity when they did their deed.

It was the night before my birthday and the German bombers kept us awake all night with their flares and their bombings and for a while it looked as if I might never get to be 43 years old. What happened in this special case was that one of our generator motors caught fire during the night and it had to happen at a very inopportune moment. When the next wave of bombers came over, the Germans naturally used the fire as a target.

The three officers and six MPs dashed to the fire to put it out. They stuck right at their work as the Germans dived on them. They stayed while the bombs blasted around them and shrapnel flew. I was sleeping about a quarter of a mile away, and the last stick of bombs almost seemed to blow me out of the bedroll — so you can visualize what those men went through. The nine of them were awarded the Silver Star a few days afterwards.

The nine lined up in a row with Colonel Gosless at the end. The commanding general came out of his tent. Colonel Gosless called the nine to attention. They stood like ramrods while the citations were read off. There was no audience except myself and two Army Signal Corps photographers taking pictures of it.

Besides the three officers, the six who received medals were Sergt. Edward Gough Brooklyn, Sergt. Charles Mitchell Brooklyn, Sergt. Homer Moore, of Nicholls, Ga., Earl Sechrist, of Windsor, Pal., PFC Barney Ewint, of Douglassville, Tex., and PFC Harold Tripp, of Worthington, Minn.

I believe the men went through more torture receiving the awards than in earning them, they were all so tense and scared. It was either comical or pathetic, whichever way it happened to strike you. Col. Goslee started rigidly ahead in a thunderstruck manner. His left hand held relaxed, but I noticed his right fist was clamped so tightly his fingers were turning blue. The men were like uncomfortable stone statues. As the General approached, each man’s Adam’s apple would go up and down two or three times in a throat so constricted I thought he was going to choke.

The moment the last man was congratulated, the General left and the whole group broke up in relief and the men went separate ways.

It was sort of dull as a spectacle but to each man it was one of those little pinnacles of triumph that will stand out until the day he dies. You often hear soldiers say, “I don’t want any medals. I just want to see the Statue of Liberty again.” But just the same you don’t hear of anybody forgetting to come around all nervous and shined up fit to kill on the evening he is to be decorated.

Evening star. (Washington, D.C.), 27 August 1943. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress.

https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83045462/1943-08-27/ed-1/