World War II Chronicle: July 6, 1943

Click here for TODAY’S NEWSPAPER

Washington has released Lefty Gomez after the former New York Yankees pitcher appeared in only one contest for the Nationals this year. Gomez won 20 or more games four times in his career, including an impressive 26-5 record in 1934, one of his two Triple Crown seasons… On page two, a former Secret Service agent has become an ace during a B-17 raid on Sicily. More than 100 enemy fighters — Messerschmidt Me-109s, Focke-Wulf Fw 190s, and Italian Macchi C.202s — jumped the formation of bombers and waist gunner Staff Sgt. Benjamin Franklin Warmer shot down seven of them during the fast and furious battle. Warmer served as the bodyguard for Treasury Secretary Henry Morgenthau Jr. before the war, and we will hear more about “Big Ben” soon…

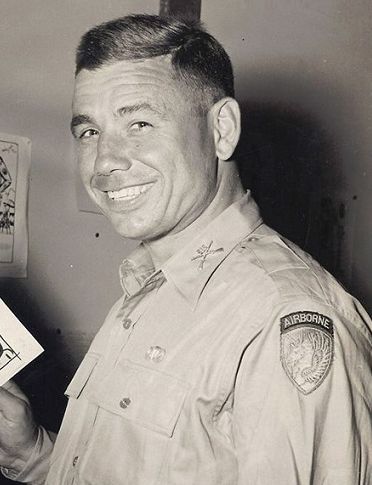

Bad news on the bottom of page two: Japanese radio reports that more than 10,000 American troops were killed on Rendova Island. Details of how a small garrison of poorly prepared defenders managed to kill more troops than were actually involved in the operation are not given… Former All-American guard and longtime Army football head coach Harvey Jablonsky is joining the paratroopers (see page three). “Jabo” was Army’s captain in 1933, when they went 9-1 and outscored their opponents 227 to 26. After earning his jump wings Lt. Col. Jablonsky will command the 515th Parachute Infantry Regiment…

George Fielding Eliot argues for a “Staff of Chiefs” to advise the president on military concerns on page 10… Sports on page 15.

Roving Reporter by Ernie Pyle

NORTH AFRICA — (by wireless) — There is one awfully important American in Africa who has been mentioned very little. That is William E. Stevenson, head of the American Red Cross over here.

Stevenson organized and ran the whole vast Red Cross setup in England. Then, starting from scratch, he built the now immense Red Cross system in Africa. And whenever the American Army goes next he will move with it and do the same thing all over again.

Stevenson’s job is unromantic but it is more vital than many a general’s. A good portion of the morale of the Army in Africa depends on his decisions. His employees run into the thousands. He spends millions of dollars a year. His daily headaches, though less important, are as numerous as General Eisenhower’s.

He has to be a pioneer, a businessman, a diplomat, a dean of women, a military expert and a wheedler of small favors, all in one. Yet until a year and a half ago he had never dreamed of organizing anything bigger than a committee meeting and had never thought twice about the institution known as the Red Cross.

Stevenson has been successful because he is smart and because he is honest, in the deepest meaning of the word. He has no sideline ambitions and no axes to grind. He wants nothing for his future out of the Red Cross, nor out of the Army nor out of Africa or England or Italy or anywhere else. He is simply serving for the duration and serving with his whole being. When it’s all over he will go back and take up where he left off — which was at the had of an outstanding young law firm in New York City.

Stevenson is tall, handsome and athletic. He looks 10 years out of college instead of 20. He is a minister’s son, but didn’t followed either of the two paths taken by so many minister’s sons. He neither turned pious or went to the dogs. He wound up as a perfectly normal well-balanced fellow, humorous and capable.

He was born in Chicago, but due to his father’s changes of pastorates he lived also in New York, Baltimore, and Princeton. Bill’s father wound up as president of Princeton’s Theological Seminary, so it was Princeton where Bill went to school, after prepping at Andover. It amuses him that recently — while faraway overseas and in no position to assume any duties — was elected a trustee of Andover, which he left 25 years ago.

Stevenson is not 42. He was just old enough to get into the Marine Corps at the tail end of the last war, and served a few months in the States. He graduated from Princeton in 1922, then went on to Oxford as a Rhodes scholar and studied law for three years there. He likes and understands the English, but he didn’t go British nor adopt the Oxford accent.

He was American champion in the 440-yard dash in 1921, and took the British championship for the same distance in 1922. Then in ’24 he went to the Olympics at Paris and ran on the 1600-meter relay that set a new world record.

There is one strange feat he is proud of. In ’21 he won the quarter-mile for a Princeton-Cornell team competing against Oxford and Cambridge. Then he went abroad, and in ’25 he won the quarter-mile for the Oxford-Cambridge team against Princeton-Cornell. That’s what is known in some circles as working both sides of the ocean.

In 1926 Stevenson returned to New York and went to work. His first job was as assistant to District Attorney Buckner. Bill went into the prohibition branch; because it paid $1000 a year more, and he needed the thousand to get married on. Buckner practiced what he enforced about prohibition, and insisted that his men do likewise. As a result the Stevenson’s couldn’t even drink champagne at their own wedding. Mrs. Stevenson still thinks it was an outrage.

A little prohibition work goes a long way, so before long Stevenson went into the law firm of John W. Davis. He stayed there till 1931, when he formed his own partnership with Eli Whitney Debevoise. They were successful from the beginning. They have had as high as 21 lawyers on their staff.

Our entrance into the war caught Bill Stevenson in that same shadowy, borderline stage of life that caught me. He is too old for combat duty and too young not to want to have a finger in the pie. He didn’t know what to do. He could have gone to Washington and donned a soldier suit with oak leaves on his shoulders and sat at a nice desk, but that somehow seemed ridiculous to him. He waited and looked around, and after a while he heard that the Red Cross needed a man to go to England.

He knew nothing about the Red Cross but thought his law experience and three years of school in England might come in handy. And it was a chance to get across the water and into the heart of things. he got the job and here he is. (More tomorrow)

Eli Whitney Devevoise is the great-grandson of Eli Whitney, the inventor of the cotton gin.

Evening star. (Washington, D.C.), 6 July 1943. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress.

https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83045462/1943-07-06/ed-1/