World War II Chronicle: May 8, 1943

Click here for TODAY’S NEWSPAPER

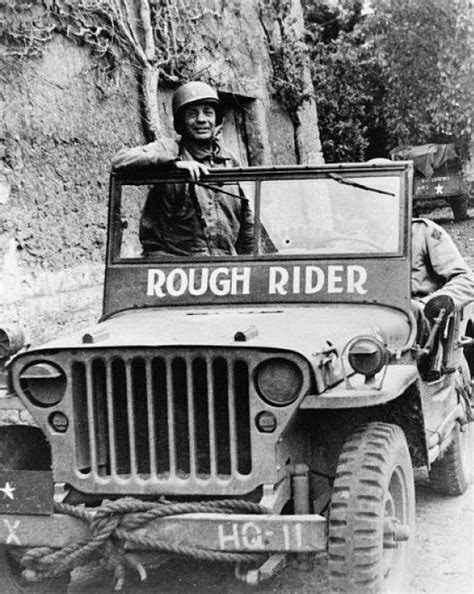

Brig. Gen. Theodore Roosevelt Jr. is pictured on page four. During the Operation TORCH landings Roosevelt commanded the 26th Infantry Regiment — the same unit he led during the First World War. As the Americans fought their way across North Africa he was promoted to Assistant Division Commander of the 1st Infantry Division…

George Fielding Eliot column on page 10… The “Torpedo 8” story continues on page 17… Sports section begins on page 22, which reports that the Washington Nationals now have the new-and-improved baseball that promises to be more lively than the dreaded balata ball. With the rubber and horse hide sources now in Axis hands, alternative options have resulted in a very dead ball, which Washington hasn’t been able to hit over the fence all season…

Roving Reporter by Ernie Pyle

IN THE FRONT LINES NEAR MATEUR — The day I’m writing about in this column is one of those days when you sit down on a rock about once an hour, put your chin in your hands and think to yourself:

“What the hell am I doing here, anyway/”

On this unforgettable Tunisian day between three and four thousand shells have passed over our heads. True, most of them were in transit, en route to somewhere else, but enough of them were intended for us to make a fellow very somber before the day was over. And just as a sideline, a battle was going on a couple of hundred yards to one side, and German machine-gun bullets were zinging past with annoying persistency.

My outfit was in what was laughingly called “reserve” for the day. But when you hear soldiers who have been through four big battles say with dead seriousness, “Brother, this is getting rugged!” you feel that you would rather be in complete retirement than in reserve.

All day we were sort of crossroads for shells and bullets. All day guns roared in a complete circle around us. About three-eights of the circle was German, and five-eighths of it American. Our guns were blasting the Hun’s hill positions ahead of us, and the Germans were blasting our gun positions behind us. Shells roared over us from every point of the compass. I don’t believe there was a whole minute in 14 hours of daylight when the air above was silent.

The guns themselves were close enough to be brutal in their noise, and between shots the air above us was filled with the intermixed rustle and whine of traveling shells.

You can’t see a shell, unless you’re standing near the gun when it is fired, but its rush through the air makes such a loud sound that it seems impossible you can’t see them. Some shells whine loudly throughout their flight. Others make only a toneless rustle. It’s an indescribable sound. The nearest I can come to it is the sound of jerking a stick through the water.

Some apparently defective shells get out of shape and make queer noises. I remember one that sounded like a locomotive puffing hard at about 40 miles an hour. Another one made a rhythmic knocking sound as though turning end over end. We all had to laugh when it went over.

They say you never hear the shell that hits you. Fortunately I don’t know about that, but I do know that the closer they hit the less time you hear them. Those landing within a hundred yards you hear only about a second before they hit. The sound produces a special kind of horror inside you that is something more than mere fright. It is a confused form of acute desperation.

Each time you are sure this is the one. You can’t help but duck. Whether you shut your eyes or not I don’t know, but I do know you become instantly so weak that your joints feel all gone. It takes about ten minutes to get back to normal.

Shells that come too close make veterans jump just the same as neophytes. Once we heard three shells in the air at the same time, all headed for us. It wasn’t possible for me to get three times as weak as usual, but after they had all crashed safely a hundred yards away I know I would have had to grunt and strain mightily to lift a soda cracker.

Sometimes this enemy fire quiets down and you think the Germans are pulling back, until suddenly you are rudely awakened by a heinous bedlam of screaming shells, mortar bursts, and even machine-gun bullets.

Here is an example of these sudden changes. As things had died down late one afternoon, and the enemy was said to be several hills back, I was wandering around some soldiers who were sitting and standing outside their foxholes during the lull. Somebody told me about a new man who had a miraculous escape, so I walked around till I found him.

He was Pvt. Malcolm Harblin, of Peru, N.Y., a 24-year-old farmer who has been in the Army only since June. Harblin is a small, pale fellow, quiet as a mouse. He wears silver-rimmed glasses. His steel helmet is too big for him.

He looks incongruous on a battlefield. But he was all right in his very first battle, back at El Guettar — an 88-millimeter shell hit right beside him, and a big fragment went between his left arm and his chest, tearing his jacket, shirt and undershirt all to pieces. But he wasn’t scratched.

He still wears that ragged uniform, for it’s all he has. He was showing me the holes, and we were talking along nice and peaceful-like, when all of a sudden here came that noise, and boy this one had all the tags on it.

Harblin dived into his foxhole and I went right on top of him. But sometimes you don’t hear them soon enough. And in this case we should have been too late, except that the shell was a dud.

It hit the ground about 30 feet ahead of us, bounced past us so close we could have almost grabbed it, and finally wound up less than a hundred yards back of us.

Harblin look at me, and I looked at Harblin. And I just had strength enough to whisper bitterly at him:

“You and your narrow escapes!”

Evening star. (Washington, D.C.), 8 May 1943. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress.

https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83045462/1943-05-08/ed-1/