World War II Chronicle: March 10, 1943

Click here for TODAY’S NEWSPAPER

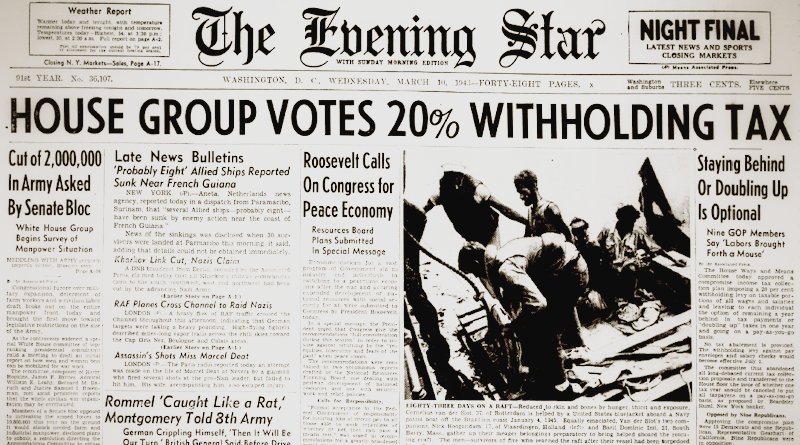

Pictured on the front page are three crew members of the SS Zaandam, who have spent 83 days drifting in the Atlantic Ocean. The 10,000-ton passenger ship was torpedoed and sunk by U-1741U-174 is sunk next month by a Bombing Squadron 125 (VB-125) Lockheed Ventura south of Newfoundland, all hands are lost. in November 1942 as she steamed 400 miles north of Brazil. Zaandam was carrying 7,000 tons of copper and chrome ore from Cape Town, South Africa to New York, as well as survivors from four different sunken ships picked up along the way. 106 of Zaandam‘s passengers are rescued on Nov. 7 by a passing ship and another 60 reach the Brazilian coast three days later. Seaman Second Class Basil D. Izzi was part of the ship’s armed guard and is among the three survivors who were picked up by a U.S. Navy submarine chaser 1,400 miles west of where their ship went down…

Maj. Gen. Charles G. Long, former Assistant Commandant of the Marine Corps, has passed away. General Long graduated from the Naval Academy in 1891 and served in about every place that Marines could go. He earned the Brevet Medal at Guantanamo Bay, Cuba, commanded a battalion at Tientsin during the Boxer Rebellion, commanded Marines in Nicaragua and at Vera Cruz. He served as officer-in-charge of the organization and distribution of Marines during the World War, for which he earned the Navy Cross…

George Fielding Eliot discusses Rommel’s plight on page 10… Sports begin on page 16, including a Grantland Rice column. Big Poison and Little Poison — Paul and Lloyd Wagner — are once again back on the same team. Paul is old. So old, in fact, he is four years older than his home state of Oklahoma. The Dodgers signed Paul in January and just yesterday traded Babe Dahlgren for Lloyd and utility infielder Al Glossop. Their father Ora was offered a major league contract by the Chicago White Stockings, but did not sign. Counting the Waners, the Brooklyn “Codgers” now have nine players over the age of 35, three of whom are over 40…

New Tigers manager Steve O’Neill will have to make due with two less players for spring training: two minor league prospects have been drafted. He only has one shortstop on the roster — 28-year-old rookie Joe Hoover. Last year four different players played 20 or more games at short for Detroit…

A former Beechcraft AT-11 Kansan crew chief named Charles E. “Chuck” Yeager graduated advanced flight training today at Luke Field (Ariz.). Flight officer Yeager will head for Tonopah, Nev. to train on Bell P-39 Airacobra fighters.

Roving Reporter by Ernie Pyle

ON THE CENTRAL TUNISIAN FRONT — The other night I was sitting in the room of Lieut. Col. Sam Gormly, a Flying Fortress commander from Los Angeles. We were looking over a six-weeks-old copy of an American picture magazine, the latest to reach us here.

It was full of photos and stories of the war; dramatic tales from the Solomons, from Russia and fight from our own African front. The magazine fascinated me and, when I had finished, I felt an animation about the war I hadn’t felt in weeks.

For in the magazine the war seemed romantic and exciting, full of heroics and vitality. I know it really is, and yet I don’t seem capable of feeling it. Only in the magazine from America can I catch the real spirit of the war over here.

One of the pictures was the long concrete quay where we landed in Africa. It gave me a little tingle to look at it. For some perverse reason it was more thrilling to look at the picture, than it was to march along the dock itself that first day.

“I don’t know what the hell’s the matter with me,” I said. “Here we are right at the front, and yet the war isn’t dramatic to me at all.”

And when I said that, Major Quint Quick of Bellingham, Wash., rose up from his bed onto his elbow. Quick is a bomber squadron leader, and has been in as many fights as any bomber pilot over here. He is admired and respected for what he’s been through. He said:

“It isn’t to me either. I know it should be, but it isn’t. It’s just hard work, and all I want is to finish it and get back home.”

So I don’t know. Is war dramatic, or isn’t it? Certainly there are great tragedies, unbelievable heroics, even a constant undertone of comedy. It is the job of us writers to transfer all that drama back to you folks at home. Most of the other correspondents have the ability to do it. But when I sit down to write, here is what I see instead:

Men at the front suffering and wishing they were somewhere else, men in routine jobs behind the lines bellyaching because they can’t get to the front, all of them desperately hungry for somebody to talk to besides themselves, no women to be heroes in front of, damn little wine to drink, precious little song, cold and fairly dirty, just toiling from day to day in a world full of insecurity, discomfort, homesickness and a dulled sense of danger.

The drama and romance are here, of course, but they’re like the famous falling tree in the forest — they’re no good unless there’s somebody around to hear. I know of only twice that the war will be romantic to the men over here. Once when they see the Statue of Liberty, again on their first day back in the home town with the folks.

And speaking of drama, I’ve just passed up my only opportunity of being dramatic in this war. It was a tough decision either way.

As you’ve seen, correspondents at last are allowed to go along on bombing missions. I am with a bomber group that I’d known both in England and elsewhere in Africa, and many of them are personal friends by now. They asked if I cared to go along on a mission over the hot spot of Bizerte.

I knew the day of that invitation would come, and I dreaded it. Not to go, brands you a coward. To go might make you a slight hero, or a dead duck. Actually, I never knew what I’d say until the moment came. When it did come, I said this:

“No, I don’t see any sense in me going. Other correspondents have already gone, so I couldn’t be the first anyhow. I’d be in the way, and if I got killed my death would have contributed nothing. I’m running chances just being here without sticking my neck out and asking for it. No, I think I won’t go. I’m too old to be a hero.”

The reaction of the fliers astounded me. I expected them to be politely contemptuous of anyone who declined to do just once what they do every day. But their attitude was exactly the opposite, and you could tell tell they were sincere and not just being nice.

“Anybody who goes, when he doesn’t have to, is a plain damn fool,” one of them said.

“If I were in your shoes I’d never go on another mission,” another pilot said.

A bombardier with his arm in a sling from flak said: “You’re right. A corespondent went with us. It wasn’t any good. He shouldn’t have done it.”

A lieutenant-colonel, who had just got back from a mission, said, “There are only two reasons on earth why anybody should go. Either because he has to, or to show other people he isn’t afraid. Some of us have to show we’re not afraid. You don’t have to. You decided right.”

I put this all down with much blunt immodesty because some of you may have wondered when I’m going along to describe a bombing mission for you, and if not, why not. I’m not going, and the reason is that I’ve rationalized myself into believing that for one in my position, my sole purpose in going would be to perpetuate my vanity. And I’ve decided to hell with vanity.

Lt. Col. Samuel J. Gormly Jr. commanded the 301st Bomb Group. You will see him again in July.

Maj. Quentin T. Quick was assigned to group headquarters.

Evening star. (Washington, D.C.), 10 March 1943. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress.

https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83045462/1943-03-10/ed-1/