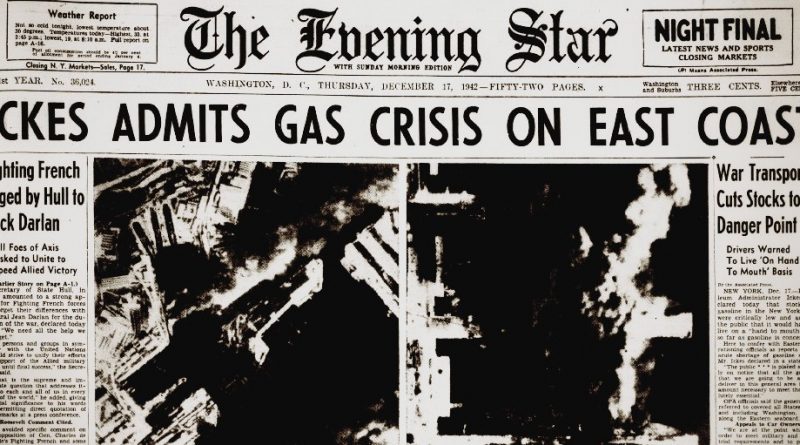

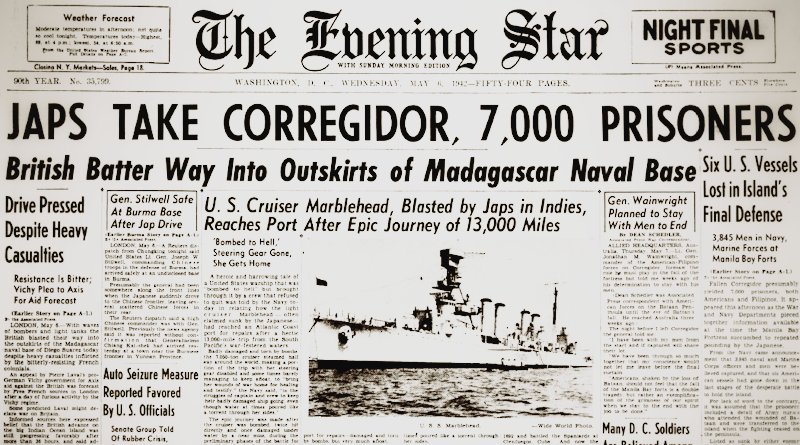

World War II Chronicle: December 17, 1942

Click here for TODAY’S NEWSPAPER

Lt. Col. Elliot Roosevelt is interviewed on page two. He has been conducting photo reconnaissance of airfields and other points of interest in North Africa and the Mediterranean. He commands the 3rd Reconnaissance Group, part of (recently promoted) Maj. Gen. James H. Doolittle’s Twelfth Air Force. The 3rd operates B-17s, F-4s (a photographic reconnaissance variant of the P-38E), and a DeHavilland Mosquito…

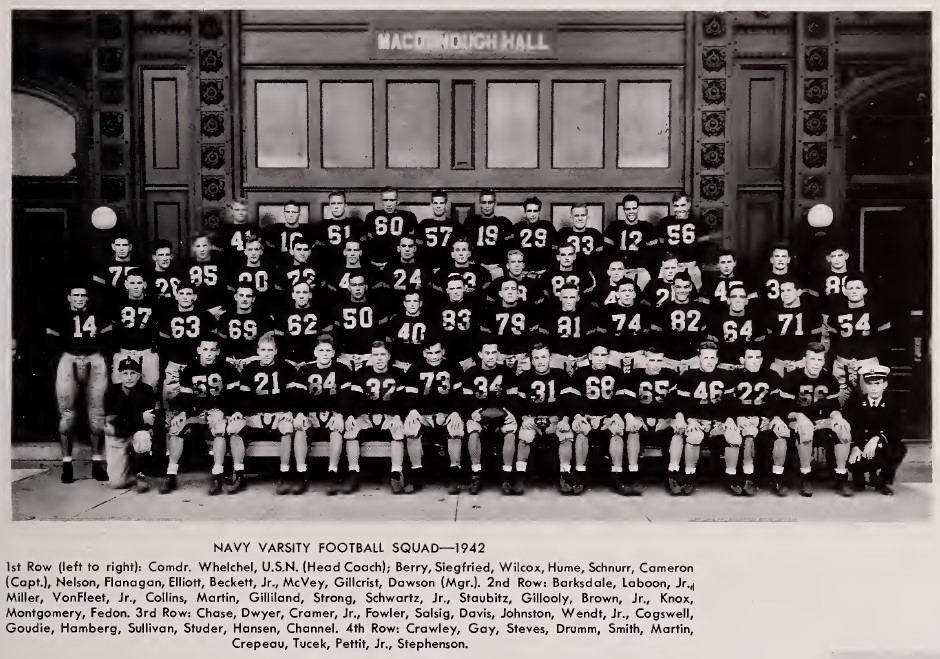

The sports section begins on page 42 which features a list of 32 Annapolis football players who lettered.

Seniors: David H. Collins is one of 317 officers and men lost when USS Spence (DD-512) capsized and sank in Typhoon Cobra on December 18, 1944… Team captain Alan R. Cameron served in the Marine Corps Reserve and attended the University of California, Berkeley before being appointed to Annapolis. Served aboard the destroyer USS Drayton (DD-366) in the Pacific Theater. Retired as a captain… John F. Laboon Jr. played lacrosse in 1943 and was selected for their All-American squad. While serving aboard the submarine USS Peto (SS-265) he earned the Silver Star for diving into mined Japanese waters — under fire — to rescue a downed American airman. He later became a chaplain and earned the Legion of Merit with combat “V” device while serving with the 3rd Marine Division in Vietnam. He returns to Annapolis as the head Catholic chaplain, and he is later head chaplain of the Atlantic Fleet. A destroyer is named in his honor and so is the Naval Academy’s Chaplain Center… Warren G. Montgomery, Arthur C. Knox, Richard C. Fedon, Fred A. Schnurr, Robert L. Wilcox, Theodore M. Gilliland, Clyde W. Siegfried, James Miller, Joseph L. Berry, Hardy B. Fowler, Oreal J. Crepeau, Howard W. Dawson (manager)

Sophomores: Hillis D. Hume returned to Annapolis as an assistant football coach and physical education instructor, retiring as a commander… Walter W. Schwartz Jr., Albert B. Channell,1 Edward M. Elliott, George C. Brown Jr.,1 Gordon P. Studer, John F. Gillooly, Vincent J. Anania

Freshmen: Benjamin S. Chase III2 plays one season with the Detroit Lions after the war… Harold A. Hamberg3 played football at the University of Arkansas before receiving an appointment to the Naval Academy. He also was captain of the national-champion track team. After sea duty on cruisers during the war he trained to become an aviator, then returned to the Naval Academy as an assistant football coach. Hamberg got to fly John Glenn from the carrier USS Randolph to Grand Turk Island after Friendship 7 splashed down in the Atlantic… William J. McVey served aboard a destroyer in the Pacific before earning his wings in 1945. Became a carrier pilot and flew 116 combat missions over Korea. Commanded the aircraft carrier USS Intrepid during the Vietnam War and served as Chief of Staff, Carrier Division Nine. Retired as a captain… The Rev. Dr. Roe H. Johnston1 became one of the founders of the Fellowship of Christian Athletes… Benjamin S. Martin,2 Joseph J. Sullivan, David A. Barksdale, Edgar B. Salsig, Grady R. Gay, Joseph T. Drumm

Roving Reporter by Ernie Pyle

WITH THE AMERICAN FORCES IN ALGERIA — A trip by troop transport in convoy is a remarkable experience. I came to Africa that way. We weren’t permitted to tell about it at the time for security reasons. But enough time has now passed that it can be written about without danger.

So this will be a series on our convoy trip from England to Africa. As you read it, you can apply it to any other convoy, for they are essentially the same, and they are sailing all the oceans this very minute.

Convoys are of three types, you might say — the very slow ones of freighters carrying only supplies; the medium-fast troop convoys which run with extremely heavy naval escort, and the small convoys of swift ocean liners which carry vast numbers of troops and depend for safety mainly on their great speed.

Ours was the second type. We were fairly fast; we carried an enormous number of troops, and we had a heavy escort, although no matter how much escort you have, it never seems enough to please you. We had both American and British ships, but our escort was all British.

I still can’t tell you what route we took or how long we were at sea, but I can say that if we had sailed the same distance due west, we could have been in New York instead of North Africa.

I got the word at noon one day that we were to leave London that night. There were scores of last-minute things to do. I’d sent my laundry off that morning and there was no hope of getting it back, so I had to rush out and buy extra socks and underwear.

The Army picked up my bedroll at 2 p.m. to take it somewhere for its mystic convoy labelings. I packed everything else in a canvas bag and my Army musette bag. Four friends came and had a last dinner with me. At leaving hour I put on my Army uniform for the first time, and said good-by to civilian clothes for goodness knows how long.

My old brown suit, my dirty hat, all my letters — every little personal thing went into a trunk which remained in London, and I’ll probably never see it again. I felt self-consious and ridiculous and old in Army uniform.

It was nighttime. I took a taxi to a meeting place designated by the Army. Other correspondents were there. Our British papers were taken away for safekeeping by the Army. We were told to take off our correspondents’ arm bands, for they might identify us as a convoy party to lurking spies, if any.

An Army car picked us up and drove clear across London through the blackout. I lost all track of where we were. Finally we stopped at a little-used suburban station and were told we’d have two hours to wait before the troop train came.

We paced the station platform, trying to keep warm. It was very dark. It seemed the train would never come. When it did we piled into two compartments and I fell asleep immediately.

We sat up all night on the train, sleeping a little but not much, because it was too cold. We didn’t know what port we were going to, but somebody told us on the way. We were surprised. Some of the boys had never heard of it.

Just after daylight our trained pulled up alongside a huge ship. We checked in at an Army desk in the pier-head, gathered our baggage and climbed aboard, feeling very grubby and cold but awfully curious.

Our party was assigned to two cabins, four men in each one. Our staterooms were nice, much better than any of us expected. They were the same as in peacetime, except that an extra bunk had been carpentered over each bed. Many officers were in cabins much more crowded than orus.

We all thought we would sail shortly after getting aboard. But we had forgotten that the ship had to be loaded first. Actually we didn’t sail for 48 hours.

All during that time one long troop train after another, day and night, pulled alongside and unloaded its human cargo. Time dragged on. Impatience was useless.

We would stand at the rails and watch the troops marching aboard. They came through the rain, heavily laden. In steel helmets, in overcoats, carrying rifles and with huge packs on their backs. It was a thrilling sight and a sad sight too in a way, to see them marching in endless numbers up the steep gangway to be swallowed into the great ship.

They came on silently, most of them. Now and then one would catch sight of somebody at the rail he knew and there would be a shout. They carried odd things aboard for men who were going off to war. Some had books in their hands, some carried violin or banjo cases.

One soldier led a big black dog. And one, I found later, carried two little puppies aboard beneath his shirt. Like the Spartan boy in the story, he was almost scratched to death. He had paid $32 for the pups and he treasured them.

The British (it was a British ship) are finicky about allowing dogs on troop transports. The officers ordered all dogs turned in. They said they’d be sent ashore and promised that good homes would be found for them.

But somehow the dogs disappeared. They were never found by the officers. And the morning we filed off the boat in North Africa and began our long march to our quarters, a black dog and two little puppies from England marched with us up the strange African road.

1: All-American in 1943

2: All-American in 1944

3: All-American in 1943 and 44

Evening star. (Washington, D.C.), 17 December 1942. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress.

https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83045462/1942-12-17/ed-1/