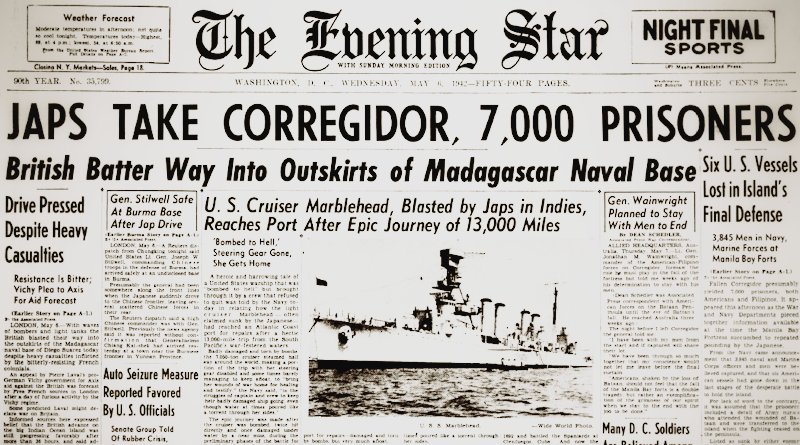

World War II Chronicle: December 26, 1941

Click here for TODAY’S NEWSPAPER

The East Coast is preparing for the possibility of enemy air raids, and silhouettes of German warplanes are on page four… Regarding Winston Churchill’s historic address to a joint session of Congress, which is printed in today’s newspaper, the British prime minister crossed a U-boat-infested Atlantic for ten days aboard the battleship HMS Duke of York. Arriving at Norfolk, Va. on Dec. 22, Churchill lived at the White House for a couple of weeks where he and Pres. Franklin Roosevelt coordinated grand strategy for World War II.

During his stay, the American and British leaders established a unified command and also declared that there would be no separate peace agreements with Axis members. The prime minister returns to Britain aboard a British Overseas Airway Corp. (the predecessor to today’s British Airways) Boeing 314 flying boat.

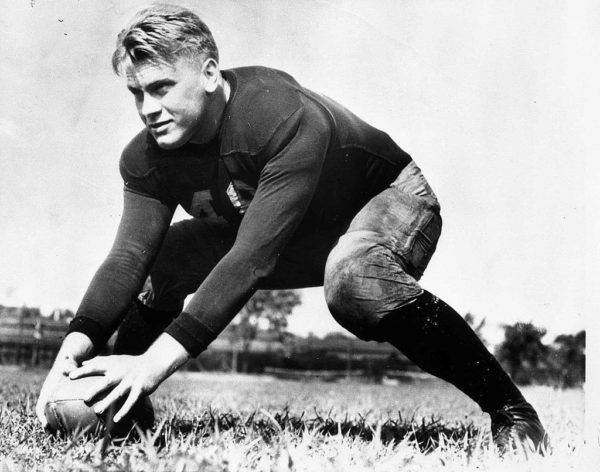

Sports section begins on page 14, which mentions the upcoming East-West college all-star football game mentioning University of Minnesota tailback Bruce Smith, who recently won the 1941 Heisman Trophy. Smith will join the Navy after graduating and becomes a fighter pilot.

“In the Far East they may think American boys are soft,” Smith said during his acceptance speech, “but I have had, and even have now, plenty of evidence in black and blue to prove that they are making a big mistake. I think America will owe a great debt to the game of football when we finish this thing off. If six million American youngsters like myself are able to take it and come back for more, both from a physical standpoint and that of morale. If teaching team play and cooperation and exercise to go out and fight hard for the honor of our schools, then likewise the same skills can be depended on when we have to fight to defend for our country.”

Tom Harmon, the 1940 Heisman winner (and father of actor — and former UCLA quarterback — Mark Harmon), flew bombers before becoming a P-38 Lighting pilot, serving in the North Africa and China theaters. During a flight to North Africa, foul weather caused his aircraft to crash in Dutch Guiana (now Suriname). The former Michigan Wolverine was the sole survivor of his crew and had to survive for six days in the jungle before reaching safety. Within a year, Harmon had to jump from another plane, this time after a dogfight over Japanese-occupied China in which he claimed to have shot down two Zeroes. Bullet holes had perforated his parachute by the time he landed in a lake and he played dead to keep the enemy from finishing him off. Harmon linked up with Chinese guerillas who helped return him to friendly lines over the next 32 days. Harmon’s bride, actress Elyse Knox used the silk and lines from the parachute that saved her husband’s life for her wedding dress.

1939 winner Nile Kinnick, of the University of Iowa, left law school to became a Naval aviator. While flying off the deck of USS Lexington on 2 June 1943, Ensign Kinnick’s F4F Wildcat developed a critical oil leak. Since Lexington‘s decks were packed with planes preparing for takeoff, the “Cornbelt Comet” had to ditch in the Carribean. When rescue crews arrived eight minutes later, they only found an oil slick.

1937 Heisman winner, Yale’s Clint Frank, went on to serve as Gen. James H. “Jimmy” Doolittle’s aide during the war. Frank was assigned to bomber groups in Italy, Africa, and England.

The first-ever Heisman Trophy winner (then called the Downtown Athletic Club Trophy), the University of Chicago’s Jay Berwanger in 1935, enrolled in flight training and became a Naval officer. University of Michigan’s star linebacker Gerald Ford (yes, the future president — and Naval officer) said “When I tackled Jay in the second quarter, I ended up with a bloody cut and I still have the scar to prove it.”

Ford served as a navigator, antiaircraft battery officer, and athletic officer aboard the light carrier USS Monterrey in the Pacific Theater. Lt. Commander Ford will remain on the inactive reserve list until 1963.

The fanatical ideologies of Imperial Japan, Nazi Germany, and the Soviet Union spawned soldiers who committed acts of barbarism on a scale never before seen in human history. The Wehrmacht killed and raped their way east to Moscow, then the Red Army did the same as they rolled towards Berlin. As we see on page 1, Imperial Japan saw no issue with bombing Manila after Gen. Douglas MacArthur declared it to be an open city. By war’s end, Japan will have committed scores of horrendous war crimes in the Philippines, exterminating over half a million Filipinos.

Treatment of the enemy operated on different tiers, depending on who fought whom: Germans and Italians captured by the Americans or British had a tremendously higher survival rate than those captured by the Soviets, while American and British POWs in German hands fared much better than their Red Army counterparts. In the Pacific Theater, Japanese forces rarely surrendered to Americans and tended to fight to the last man. Part of this can be attributed to the fanatical warrior ethos of the Japanese military, who would prefer going out in style with a bansai charge or seppuku ritual suicide.

But there would undoubtedly be more Japanese prisoners of war if it weren’t for the last-ditch tactics of the Japanese wounded and would-be captives. American soldiers and Marines soon learned that a Japanese soldier would often pretend to surrender, only to pull a pin on a hidden grenade when American GIs came within lethal range. It shouldn’t be too much of a stretch to understand that once you’ve seen a Japanese soldier kill a few of your buddies you won’t fall for that trick again. Additionally, mortally wounded (or non-wounded) Japanese troops would appear to be dead, only to spring up during the mopping-up phase and take an enemy or two out with them. Before long, U.S. troops started “possum patrols,” shooting Japanese left on the battlefield — dead or dying. As horrible as shooting wounded soldiers may sound, Japan’s savage conduct left Americans without much of a choice.

Evening star. (Washington, D.C.), 26 December 1941. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress.

https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83045462/1941-12-26/ed-1/