World War II Chronicle: November 18, 1941

Click here for TODAY’S NEWSPAPER

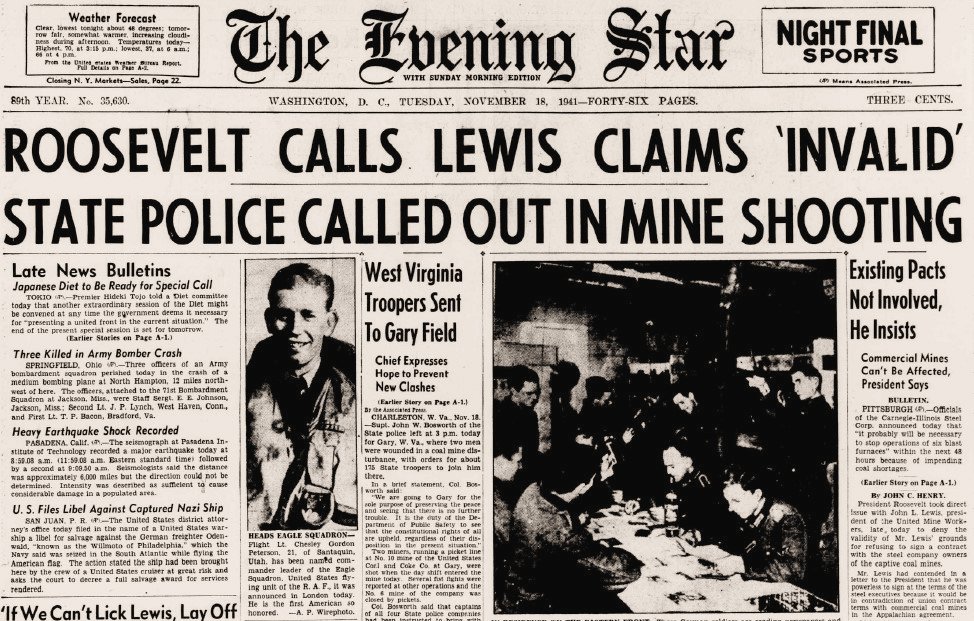

Pictured on the front page is Flight Lt. Chesley G. Peterson, the first American to become squadron leader in the Royal Air Force. Read the Dec. 5, 1941 Chronicle for more on Peterson… World War I flying ace Generaloberst Ernst Udet has died. Udet was personally recruited by Manfred von Richtofen — the “Red Baron — and finished the war with 62 kills (second only to Richtofen). There is more to the story of Udet’s death and his funeral will be eventful, click here for more…

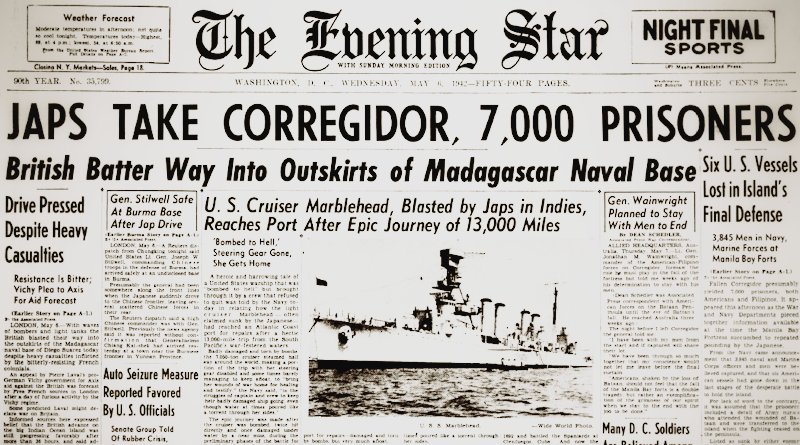

Pictured on page five is the prize ship Odenwald. While searching for blockade runners in the Caribbean, the cruiser USS Omaha and destroyer USS Somers spotted a cargo ship flying U.S. colors but behaving oddly and whose sailors looked “uniquely un-American.” When Omaha attempts to contact the crew, the ship’s crew attempt to sabotage the vessel and a boarding crew is sent over. The captured ship turns out to be the German Odenwald, transporting raw rubber and tires from Japan. The sailors from the boarding party are each awarded $3,000 as bounty from the seized cargo and everyone else involved receives two month’s pay – the last time U.S. sailors will be awarded prize money… Sports section begins on page 15…

How were our forces on Hawaii caught so completely by surprise on Dec. 7, 1941? With hindsight it is easy to see what could have been done differently and who was responsible, as it seems an integral part of our human nature to pick out scapegoats. We knew that war with Japan was inevitable, and some predicted where the hammer would fall. But when? And how?

A thorough analysis of the Imperial Japanese Navy’s strategy and tactics shows that while we could have handled things differently, the effectiveness of the Hawaiian Operation — as the Japanese called it — is mostly due to the outstanding execution by the enemy, not only in carrying out the attack, but in their preparation as well.

While American signals intelligence was good — we had broken the Japanese Naval code — we couldn’t decipher every transmission, and often could only understand parts of the intercepted message. Sometimes none of the message could be read, but analysts could still piece together information from the amount of traffic and the direction it came from. To complicate matters, different listening posts sometimes gave conflicting reports.

On November 1, 1941 the Japanese Navy changed the entire method of broadcasting messages to the fleet — and how ships acknowledge having received the communication. This added another layer for our analysts to sort out. The Japanese used code words for ships and locations, and we had figured out many of them. But the Japanese staged an exercise in early November 1941 and issued new codenames for the fleet. Adding yet another layer of complexity, the ships about to secretly sail for Hawaii continued to use their old codenames to send phony traffic.

The ear of an experienced analyst can also become so highly tuned to traffic that they recognize the intricacies of a particular operator tapping the message. So the radio operators for ships about to depart were sent ashore to continue sending traffic while their ships slipped away under radio silence. The Japanese knew American cryptoanalysis was good, and it wouldn’t take a signals intelligence genius to notice that half a dozen carriers, two battleships, and a supporting armada of ships suddenly went silent.

To the American listening in, the volume of traffic, names, directional bearings… it all checked out: As far as the we knew, the carriers and battleships were in fact still in Japanese home waters conducting a drill. The Japanese had slipped the net.

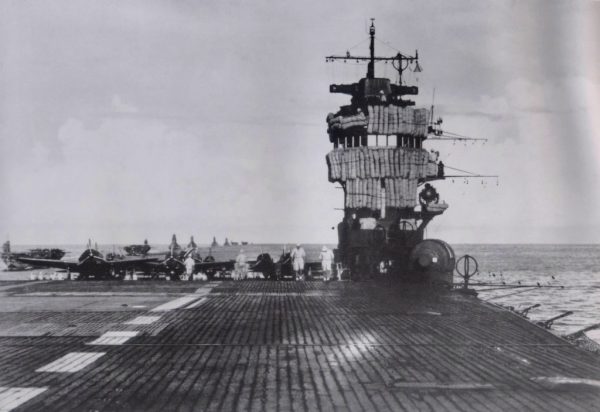

On Nov. 18, 1941, the aircraft carrier Kaga was not in Sasebo, but was pulling into Saeki Wan, on Kyushu Island. There her crew loaded 100 specially modified Type 91 torpedoes that Mitsubishi’s ordnance works fitted with breakaway wooden nosecones that, together with wooden fin covers, would allow the torpedo to be dropped from low altitude to run in the shallow water of Pearl Harbor.

Four other different Japanese aircraft carriers — Hiryu, Soryu, Shokaku, and Zuikaku — made similar stops at Saeki that day before silently slipping out of the harbor and turning north.

Akagi had already visited Saeki, where Adm. Isoroku Yamamoto boarded the flattop and briefed a group of officers who would carry out the surprise attack. Afterwards, Akagi sailed for the secret assembly area in the Kuriles.

The Kido Butai was forming.

Evening star. (Washington, D.C.), December 18, 1941. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress.

https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83045462/1941-11-18/ed-1/