Ocean Station NOVEMBER to the rescue

On the evening of 15 October 1956 a Pan American Airlines Stratocruiser named Clipper Sovereign of the Skies lifted off from Honolulu, headed to San Francisco on a 2,000-mile flight. 24 passengers and seven crew were flying the final leg of their around-the-world flight, but still had 2,000 miles of open ocean to cross.

4 hours, 38 minutes into the nine-hour flight Capt. Richard Ogg climbed from 13,000 feet to 21,000. After leveling off, Clipper‘s Number 1 engine started spinning out of control. The cockpit suddenly jolts and the high-pitched noise of the runaway engine can be heard inside the cabin. The crew works to bring the engine RPMs down, but can’t feather the propeller to slow the blades down. Capt. Ogg is left with no choice but to kill the engine by cutting off the flow of oil.

Down to three engines with 1,000 miles to fly, the Pan Am crew now had to contend with a propeller that is now creating a tremendous amount of drag, slowing down the plane and requiring the remaining three engines to increase their power — and fuel consumption — to compensate.

Good news/bad news

The bad news: the Pan Am clipper has just reached the “point of no return” — halfway between Honolulu and San Francisco. The good news: 50 miles to the east is Ocean Station NOVEMBER, a spot in the Pacific where a Coast Guard cutter kept station, providing weather reports, relaying communications traffic, and is on call for search and rescue duties. Within moments of the incident, the Pan Am crew notified USCGC Pontchartrain (WHEC-70) of the situation. Although it was still the middle of the night, seas were calm if the pilot had to ditch in the ocean.

Now traveling much slower and burning more fuel, flight engineer Frank Garcia Jr. calculated that the plane would be about 250 miles short of both Hawaii and California. Ogg would have to ditch in the ocean.

Meanwhile, Pontchartrain laid out a string of lights marking a runway for Ogg to land on. Clipper still had plenty of fuel to keep them airborne until daylight, which increased their chances of a successful ditching, so Ogg flew a holding pattern over the Coast Guard cutter and burned off fuel, making the aircraft more buoyant.

To make matters worse, the Number 4 engine backfired while the crew orbited and had to be shut down. Ogg had just two engines left to keep the Stratocruiser aloft.

Ogg ordered all passengers and crew to strap in towards the front of the cabin, thinking that the rear of the fuselage might come apart once the plane hit the waves. As the sun rose, Pontchartrain hauled in their lights and laid out a makeshift runway of firefighting foam, which would lessen the chances of a fire and gave Ogg a target to land on.

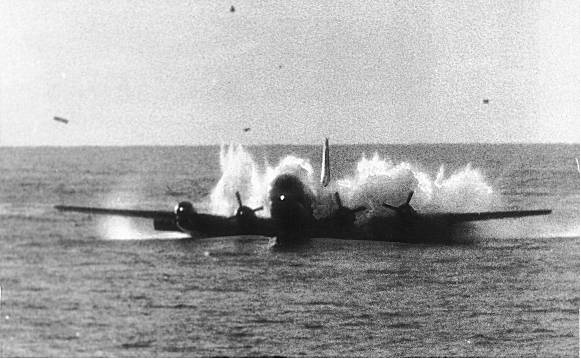

At 6:15 Hawaiian Standard Time the Clipper Sovereign of the Skies touched down, skipping off the water then slamming to a sudden stop. The rear fuselage did in fact separate, but thanks to the superb airmanship of the crew everyone lived. In fact, there were only a handful of minor injuries.

20 minutes after ditching in perhaps the most remote places on the planet that planes travel, 1,000 miles away from anywhere, the Clipper slipped beneath the waves. But by then, all passengers and crew were safely aboard the Pontchartrain and steaming towards San Francisco.

In 1969, a C-97 Stratofreighter (essentially the military’s version of the Boeing 377 above) was enroute from Travis Air Force Base (Calif.) to Hawaii’s Hickam Air Force Base on their way to Cam Ranh Bay, South Vietnam when the crew experienced a similar problem. One of the 28 cylinders in the Number 4 engine cracked its head and threatened to disintegrate the propeller. The crew managed to feather the engine and continued with three engines as they reached the halfway point of their flight.

No sooner than the crew finished their post-emergency checklist, the crew chief reported that the Number 2 engine was on fire. Now down to two engines — which due to their location provided asymmetrical thrust that made flying extremely difficult — the crew turned around and headed for San Francisco. Ocean Station NOVEMBER was again called on for a potential rescue at sea as the C-97 dropped out of the sky.

“The C-97 was a good ditching airplane, averaging 11 minutes of float time. That was marginally comforting,” recalled William Campenni, (Col. (ret.), U.S. Air National Guard) who served as copilot on this particular Air National Guard flight. However, “a C-97 that had ditched off the Azores floated for 10 days until it was deliberately sunk as a hazard to shipping. It wasn’t rocket science to compute that 10 days factored into that 11-minute average meant those other C-97s must have sunk like stones.”

The crew applied full takeoff power to stay airborne, finally leveling off at 1,000 feet. To keep from getting wet, they would have to keep constant pressure on the rudder pedals and the throttle at full power — for the next four hours. They made it past the Coast Guard cutter, who called for a C-130 rescue plane to fly west and meet them in case the remaining two engines gave out But as the fuel burned off, the Stratofreighter became lighter and they could back off the throttles.

The two engines held out and got the crew back to San Francisco. The engines on the C-97 were so unreliable that crews jokingly called the Stratofreighter the “Boeing Tri-Motor.”

Sounds a bit like Ernie Gann’s, “The High and Mighty”

Great trading all around!