Lewis and Clark (virtual) Ride: Bushwackers, dysentery, and hemp bales

[This is part seven in a series of articles documenting my virtual bike ride across America, following the route of the Lewis and Clark expedition. For previous posts, click here.]

Tracing Meriwether Lewis and William Clark’s route to the Pacific from over 200 years ago, I strap back into the pedals of my PROFORM Tour de France bike and pick up the trail in modern-day Saline county, just west of where the Chariton River empties into the Missouri River. My virtual route, which follows the river as closely as roads allow, meanders through the western portion of Missouri’s “Little Dixie” region. This part of the “Show-Me State” got its name from the plantation owners that migrated here from Kentucky, Tennessee, and Virginia in the 19th Century, bringing their slaves with them, and establishing hemp, tobacco, and cotton farms.

The explorers had been traveling upriver for a month at this point, and Capt. Clark writes that the men were “much aflicted [sic] with boils and several have the Decissentary [dysentery].”

Clark attributes their afflictions to the muddy water of the Mississippi, but know that while you would be hard-pressed to find men with the knowledge and experience of Lewis and Clark when it comes to survival in the wild, Louis Pasteur’s germ theory wouldn’t be developed for another half-century. The men had to drink untreated water, and the game they killed had to be preserved by “jerking.” This meant that animal meat had to be cut up into strips and dried by the wind and sun. If it rained, which happened for weeks at a time west of the Rockies, their meat got soggy and would collect bacteria and begin to spoil.

With no ovens, no water filters, no regular bathing, and no change of clothing, bacteria were having a field day on the explorers. Plus the mosquitoes were miserable — or as Clark writes in his June 28th entry: “misquiter verry bad.” His complaints about mosquitoes (which Clark rarely spells the same way more than once) will appear frequently, and increase in severity, as they head west. All things considered, it’s amazing that the only casualty of the trip was a man whose appendix burst, which could just as easily kill a hiker today.

There probably wasn’t a lot of time to fuss about “misquiters” though, as the men were busy fighting the swift, dangerous, and often unpredictable currents; propelling their vessels upriver while avoiding driftwood and sandbars, which could overturn or sink the crafts; cooking; making equipment to replace damaged items like clothes, oars, rope, and sometimes boats; hunting for meat and fresh water; heading ashore and scouting the territory they traveled through; obtaining specimens for scientists to study; drying out soaked items; and journaling everything.

All this activity required a lot of protein. A lot.

The Corps of Discovery worked so hard that it took about nine pounds of meat per day to feed each man. Clark wrote that it took four deer, or one elk and a deer, or one buffalo to keep the men fed each day. While in Missouri, the men mostly relied on deer, of which they would kill just over 1,000 during the trip. The men had already spotted signs of buffalo around the modern-day site of Boonville, Mo., but would not see one until near present-day Kansas City. They were also heading into elk territory at this point of the journey.

Bushwackers and Jayhawkers

With all the southerners inhabiting Little Dixie in the 1860s, this area was deeply supportive of the Confederacy during the Civil War. Little Dixie wasn’t home to any major battles, but Union supporters and area slaves were plagued by bloodthirsty “bushwackers,” and the devastation brought upon western Missouri by the Federal efforts to defeat the partisans would haunt the region for decades to come.

Following the Camp Jackson Affair (see part six of the series), small bands of pro-Confederate bushwackers formed across rural Missouri, ambushing Union troops, disrupting communications, fighting abolitionist Kansas “jayhawkers,” and terrorizing Unionist families in Missouri and Kansas.

The bushwackers were so effective that to restore order in western Missouri, the Union had to take drastic action: first, they authorized the arrest of family members suspected of aiding the partisans. Later, they forcibly removed tens of thousands of Missourians that could not prove their loyalty to the Union, resettling families in Kansas or in Union-friendly towns. Property was often plundered, while homes and countless acres of crops were burned.

Some men became partisans for the cause and others did so for fun and profit — and carried on after the war.

Many members of the infamous James-Younger Gang got their start as bushwackers. Frank James became one after serving in Gen. Sterling Price’s Missouri State Guard, fighting alongside Cole Younger (who would later join the regular Confederate Army) under legendary bushwacker Paul Quantrill. His brother Jesse joined in 1864, when he became 16 years old, and served under Archie Clement.

On May 15, 1865, Clement and Jesse James tried to surrender to Union cavalry troopers after a brief skirmish in Lexington, Mo. It wouldn’t be too much of a stretch to suggest that the Union men had some reservations about whether they were actually trying to surrender, because James received a life-threatening shotgun blast to the chest. The end of the Civil War, however, wasn’t the end of the road for the bushwhacking lifestyle of Clement, Younger, and the Jameses: soon a string of area robberies would be attributed to the group.

Then, on election day in 1866, Clement led a gang of 100 bushwackers into Lexington, driving off Republican supporters with intimidation and gunfire. This led the governor of Missouri to deploy a platoon of state militia to the town to apprehend Clement. He would die in a gunfight with the troops the following month, refusing to surrender.

Civil War

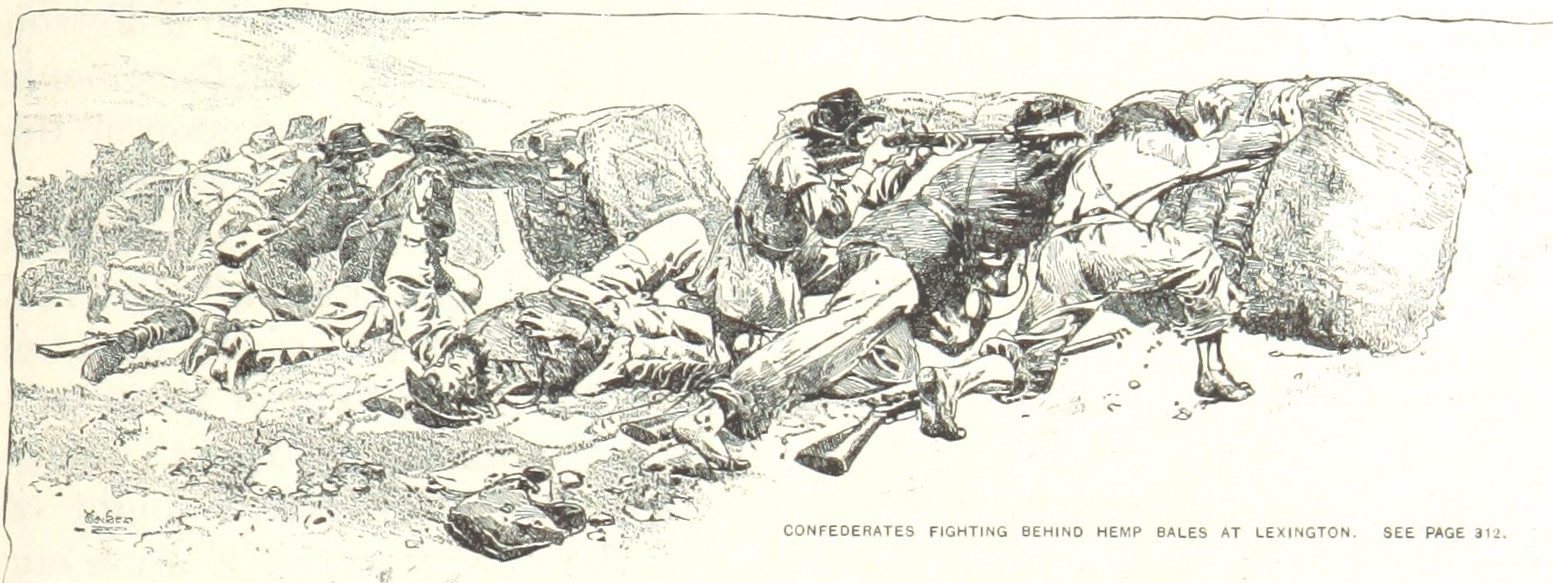

Lexington was the site of two battles. Following their victory over the Missouri State Guard in the Battle of Booneville, Federal troops occupied Lexington and fortified the Masonic College. On Sept. 12, 1861, Gen. Price’s 15,000-strong State Guard force — including a young Private Frank James — began arriving and the Union defenders retreated to their fortifications around the college after a brief skirmish. Col. James A. Mulligan’s “Irish Brigade” were well dug-in: surrounded by trenches, stakes, mines (crafted from the college’s water pipes), lunettes, and ten-foot-high ramparts. But they would soon be outnumbered nearly five-to-one when the State Guard arrived in force.

Soon the Federal troops were surrounded, and when driven back to their defensive lines by enemy artillery, they lost access to their water supply. On the 20th, Price was ready to put an end the siege; State Guard artillery placed the college under heavy fire, and one of the cannon balls struck the courthouse, which 158 years later holds the distinction of Missouri’s oldest courthouse still in use. The cannonball remains stuck in the column.

While the artillery poured fire into the defenders, Price’s infantry used hemp bales they had soaked overnight in the Missouri River as mobile breastworks, impervious to both heated cannon shot and bullets. The troops rolled the bales right up to the Union lines, forcing the thirsty garrison to surrender.

On Oct. 19, 1864, Gen. Price was back in Lexington — this time as a major general in the Confederate Army. The goal of Price’s Missouri Raid was to return Missouri to Confederate control, or at minimum, damage President Abraham Lincoln’s re-election chances. Following his victories over smaller Federal forces at nearby Boonville and Glasgow, Price’s men plowed through Union pickets in what amounted to more of a skirmish than a full-blown battle.

Following their defeat at Lexington, the Union troops fall back to Jackson County, where they will clash again with Price’s troops at Independence, Mo. Ultimately, Price’s expedition will come to an end when he finally finds himself outnumbered in the Battle of Westport, sometimes referred to as the “Gettysburg of the West.” Price’s tattered army retreats first to Kansas, then heads for Mexico. The former Missouri governor and veteran of the Mexican-American War will return to his home state after his idea of a Confederate colony fails, and he will die in poverty in 1867.

At this point of my virtual journey I have pedaled 321 miles and have somewhere around 3,500 to go.