Lewis and Clark (virtual) Ride: Boonslick Country to Missouri’s Grand Divide

[This is part six in a series of articles documenting my virtual bike ride across America, following the route of the Lewis and Clark expedition. For previous posts, click here.]

In this post, I pick up the trail west of Jefferson City, Mo. and continue along the Missouri River until reaching the Chariton River.

Along the way is the town of Boonville, Mo., which was the site of a tiny battle that had a huge impact on the Civil War.

On May 10, 1861, just days after the first shots of the Civil War were fired at Fort Sumter (S.C.), several hundred Missouri militiamen were drilling at Camp Jackson, just outside the city limits of St. Louis. A pro-confederate force had recently overrun the federal arsenal at Liberty, Mo., and Brig. Gen. Nathaniel Lyon suspected the force amassed at Camp Jackson was going to seize his large arsenal in St. Louis and he ordered his federal troops to capture the Missouri Volunteer Militia members.

As the Union troops marched their prisoners through town, they were harassed and pelted with rocks and other objects by a secessionist mob. Lyon’s men eventually opened fire on the crowd, killing 28 civilians and wounding dozens more. Missouri’s pro-confederate governor Claiborne Jackson and Missouri State Guard commander Maj. Gen. Sterling Price (a former brigadier general of volunteers and veteran of the Mexican-American War who opposed secession until the Camp Jackson incident) met with Lyon and told him that his federal troops were not to travel beyond St. Louis. Lyon responded by saying their demand “meant war” and declared his men would have free passage throughout the state. He allowed Jackson and Price safe passage out of St. Louis and the pair fled west to Jefferson City. However, Lyon and his force of U.S. Army regulars and Missouri militia were hot on their tail.

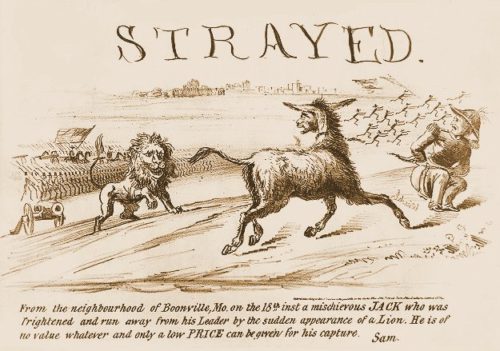

Realizing they could not defend the state capital, Jackson and Price kept moving west until they reached Boonville. There, they hoped to hold off the federal troops until enough volunteers could be mustered in nearby Lexington to defeat Lyon’s force and ultimately bring Missouri into the Confederacy. Lyon captures Jefferson City on June 13 without a fight. Four days later the two armies meet up at Boonville for a small but strategically significant engagement, with a dozen Union casualties and around 100 for Price’s State Guard. With Jackson on the run, Missouri declares his seat vacant and a pro-Union state government takes over. The entire Missouri River is now under federal control, and the border state would no longer be in danger of joining the Confederacy.

“Insignificant as was this engagement in a military aspect, it was in fact a stunning blow,” wrote Thomas L. Snead, who served as Jackson’s aide-de-camp and Price’s chief of staff, “and one which did incalculable and unending injury to the Confederates.”

Lyon continues to chase Price’s State Guard southwest until his troops are defeated in the Battle of Wilson’s Creek and Lyon becomes the first general killed in the Civil War.

Price would return to Boonville in 1864, capturing the town from Unionist forces during his failed Missouri Expedition, but withdraws the following day .

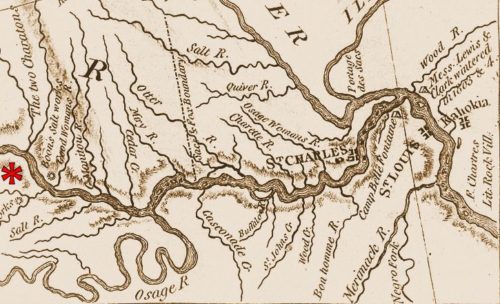

Across the Missouri River from Boonville is where famous frontiersman Daniel Boone’s sons Nathan and Daniel Morgan established a business distilling salt from the area’s saltwater springs, at the site of Boone’s Lick State Historic Site. 200 years later, U.S. Highway 40 traces it’s roots to the route Boone’s sons used to ship salt back to St. Charles, known as Boone’s Lick – or Booneslick – Road.

In 1816, the town of Franklin (named after founding father Benjamin Franklin) sprung up next door to the Boone’s springs. A man named William Becknell set out from Franklin in 1821, loaded with goods he hoped to trade in the town of Santa Fe (modern-day New Mexico), which was then part of the brand-new country of Mexico – having just secured their independence from Spain. Upon his return, Becknell had pioneered a trail that would become a lucrative trade route, and later an important highway and railroad route. Prior to becoming the “Father of the Santa Fe Trail,” Becknell had served under Capt. Daniel Morgan Boone (mentioned above) during the War of 1812 in the United States Mounted Rangers.

Also hailing from Franklin was ousted governor Jackson, who raised a company of volunteers for service in the Black Hawk War of 1832. The outfit elected Jackson as their captain.

Roughly following in Price’s footsteps, I come across the one-horse town of Glasgow. Back in 1864, elements of Gen. Price’s army laid siege to the town and attacked the Union garrison of 800 men from several sides. The Confederates seized over 1,000 guns, supplies, and 150 horses and permitted the defeated Union soldiers to return to friendly lines back at Boonville.

This leg of my journey wraps up south of where the Chariton River empties into the Missouri River. The Chariton is called Missouri’s “Grand Divide” as streams east of it flow into the Mississippi and streams west discharge into the Missouri.

Lewis and Clark reached this point on June 10, 1804. The Corps of Discovery members that kept journals all mention how difficult this section of the river was. Pvt. Patrick Gass wrote in his June 9 entry that they got stuck on a log, which “immediately swung [the keelboat] round, and was in great danger; but we got her off without much injury.” Soldiers jumped into the river and swam ashore hauling ropes that they used to pull the boat away from the obstacle.

Before volunteering for the Corps of Discovery, Gass was part of the crew that built the log cabin in Pennsylvania that a young James Buchanan grew up in, and he became acquainted with the future president while on the job. He fought Indians with the Pennsylvania rangers, served under Maj. Gen. Alexander Hamilton in the U.S. Army, and also fought in the War of 1812. His carpentry skills proved invaluable to the expedition, supervising the construction of canoes, forts, and wagons along the way.

After pedaling 249 miles, I still have 3450 miles to go before reaching the Pacific Ocean. Click here to see previous posts along my route.